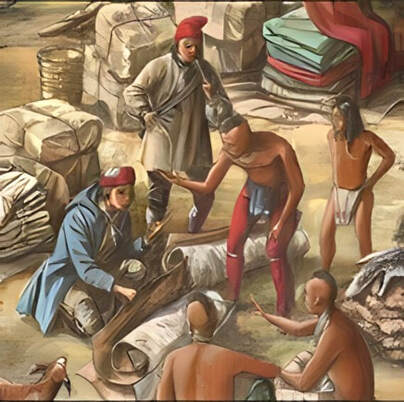

For thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans, the Mi’kmaq, the indigenous people of Nova Scotia, lived, hunted, and fished throughout parts of the maritime provinces, in a region that came to be known collectively as Mi’kma’ki. The particular district in which the shores of the Minas Basin and Grand Pré are located was called Sipekni’katik, the name by which today’s Mi’kmaq still know it.

|

|

Mi’kmaq

|

|

|

Their presence in the broader landscape is confirmed from traditional, archaeological, and ethnographic sources. The archaeo-logical discovery in 2009 of a 4000 year old stone gouge at Horton Landing provides the earliest date of use of the area by the ancestors of the Mi’kmaq. The Minas Basin figures prominently in the history, legends, and spirituality of the Mi’kmaq, especially Cape Blomidon, which has been for centuries the dominant feature on the landscape in the overall Grand Pré area. This is the setting for the stories of Glooscap – the most important Mi’kmaq hero – including Glooscap and the Whale, Glooscap’s battle with the Beaver, and Glooscap and Lazy Rabbit. These stories and more confirm the importance of the Minas Basin and the lands surrounding it for the Mi’kmaq. |

Archaeological and ethnographic evidence shows that the Mi’kmaq had settlements in the area, particularly on nearby Oak Island at Melanson along the Gaspereau River, and at Horton Landing, confirming their presence in the area over several thousand years. Among the many important Mi’kmaq sites in the Grand Pré area is a burial ground on Oak Island. The Minas Basin falls within range of a regional trading network that brought chert mineral, a stone similar to flint and used to make tools, and traded stones and products from the sea.

|

The Mi’kmaq typically harvested a wide range of resources in estuarine environments like the one that existed at Grand Pré: water-fowl, fish, shellfish, sea mammals, and medicinal plants. It is almost certain that the Mi’kmaq took the resources they needed from the area on a seasonal basis, such as when certain fish species were abundant in adjacent waters and when the huge flocks of migratory birds came to the area to rest and fatten up.

While the Acadians still had some connection with the French colonies in Canada as semi-nomadic Algonquian people, the Mi’kmaq’s homelands, which they called Mi’kma’ki, spread across Nova Scotia. With this widespread territory, and their hunters’ proclivity for travelling far and wide, the Mi’kmaq became closely tied with the fur trade in French towns like Montreal and Quebec.

|

|

Chief Membertou greeted Samuel de Champlain as French families arrived in what would become Nova Scotia. The first winter was a difficult one and many died of scurvy, but the native Mi’kmaq people welcomed the Acadians, they traded with them and taught them how to survive the unfamiliar land, they showed the French settlers that drinking pine needle tea that is rich in vitamin C, will stave off scurvy, and yarrow reduces fevers, while in turn, a herb called plantain made its way to Nova Scotia hidden in the wool of sheep, and was used to draw out infections and as a much-needed salve for mosquito bites.

|

Over centuries of colonization efforts in Canada, the French had learned how to get along fairly well with the Mi’kmaq. Much like other Algonquian nations, gift giving ceremonies played a large role in Mi’kmaq diplomacy and trade, a custom the French colonists learned to adopt in their dealings with their new neighbors and trading partners. This larger pattern of Franco-Mi’kmaq relations played out in Acadia as well. Not only were Mi’kmaq “concepts of gift, gratitude, and reciprocity… understood by the Acadian people,” they also earned points for not taking Mi’kmaq lands. In fact, many historians agree that the “Acadians and Mi’kmaq worked together and did not interfere with the land the other wished to inhabit, as Acadians lived on the marshlands and the Mi’kmaq in the uplands.

|

The rare, harmonious relationship between the two races was peaceful and beneficial, a new community partnership resulted in many mixed marriages and even mixed languages and built strong longstanding ties in the community of Grand Pré until the modern day.

|

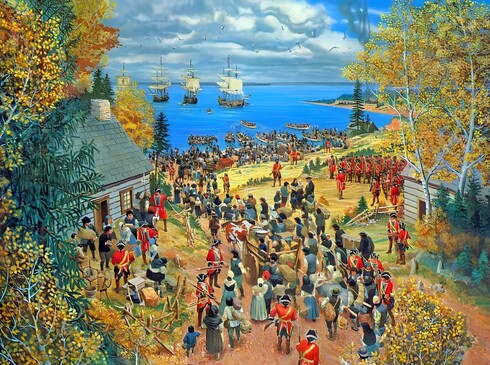

Then, in June 1755, a piece of propaganda fell into British laps. After capturing Fort Beauséjour, Charles Lawerence counted around 270 Acadian militia men among the French soldiers who surrendered. His paranoia about the “Acadian problem” now seemingly verified, Lawrence ordered the expulsion of the Acadians from Nova Scotia. As war began, Britain took aim at an important link in the French supply chain – the Mi’kmaq-Acadian alliance. Early on, British officials deported small numbers of Acadians and offered bounties for Mi’kmaq scalps. But, as the war continued, Britain became ever more convinced that the Acadians remained loyal to the French. If the Acadians decided to aid their French cousins using their Mi’kmaq trading networks, or fought alongside the Mi’kmaq in battle (which they’d done before), the Acadians could have done some damage to British security.

|

|

In typical British fashion, they attempted to take the land as their own, and paid no mind to indigenous forms of respect and diplomacy. These British encroachments on Mi’kmaq land alienated the inhabitants of Mi’kma’ki, so when the French and Indian War broke out, the Mi’kmaq counted themselves among the ‘Indians’ who sided with the French.

|

|

Having addressed the Acadian threat by deporting most of the Acadians, the British authorities sought to address the Mi’kmaq threat by signing treaties with them throughout the 18th century. Indeed, the Mi’kmaq had been allies of the French and the Acadians. During the Deportation, the Mi’kmaq helped some Acadians escape into the forest and in many instances sheltered them as their own. For the British Crown, these treaties meant peace with the Mi’kmaq and the freedom to settle in Nova Scotia with populations whose loyalty was unquestionable.

|

|

|

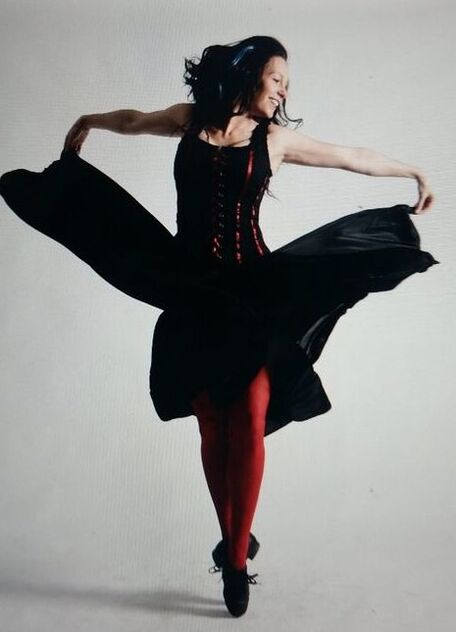

Friendship Celebration |

|

In 2017 on Canada's 150th anniversary, a celebration to rekindle the 400 years of friendship between Acadians and the Mi'kmaq was organized at Grand-Pré National Historic Site.