The Landscape of Grand Pré is an exceptional living agricultural landscape, claimed from the sea in the 17th century and still in use today applying the same technology and the same community-based management.

|

|

Historical Timeline

|

|

|

|

The Evolution of an Agricultural

|

|

Since the 1680s, when a small group of Acadian settlers first arrived in the area and called the vast wetlands la grand pré, the human history of Grand Pré has been linked to its natural setting and the exceptional fertility of this land by the sea.

|

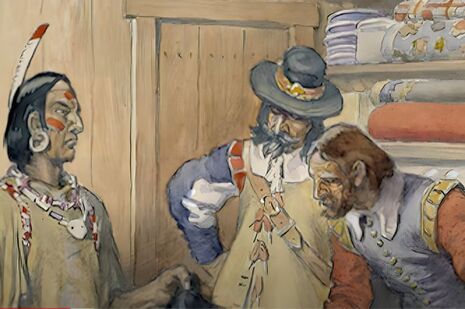

Between 1680 and 1755, the Acadians took on the project of excluding the sea and claiming the highly fertile tidal marshes. With the coming of the Acadians, and the dyking of some of these marshes, that fertility became available for agriculture. The pioneers were isolated. They were far from their ancestral land, and were often ignored by the French and British authorities who administered the region. The pioneers therefore developed a close relationship with the Mi'kmaq, the indigenous people of Nova Scotia, not only at Grand-Pré but elsewhere in Acadia. In the seventy-odd years the Acadian community of Grand-Pré introduced an approach to environmental management that, incidentally, had already been perfected elsewhere in Acadia. They adapted methods that in Europe had been applied to wetlands and salt marshes to assure sustainability for the community. |

Faced with the highest tides in the world, the Acadians of Grand-Pré transformed - through three generations of hard work - over 1,300 hectares of alluvial land into farmland. It was then - and remains today - some of the best farmland in North America. As the Acadians became more familiar with the local environment and began to transform the intertidal zones. All these factors contributed to the development of a new, distinct identity. Even though they were of French origin, these pioneers came, in the second half of the 17th century, to see themselves as part of Acadia, as Acadians. |

|

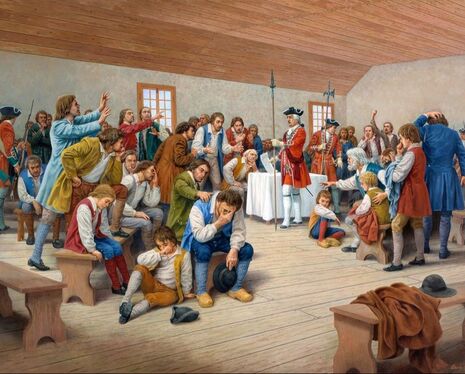

On 4 September 1755, Lt.-Col. Winslow issued a call for all men and boys aged 10 and older to come to the parish church at three o’clock the next afternoon to hear an important announcement. On 5 September, 418 Acadian males of Grand Pré proceeded to their parish church – now surrounded by a palisade and controlled by armed soldiers – to hear the announcement. Once they were inside, Winslow had French-speaking interpreters tell the assembled men and boys that they and their families were to be deported. |

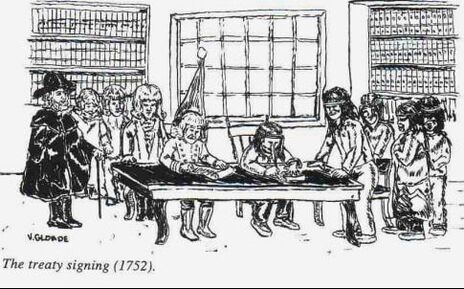

The Treaty of 1752, signed by Jean Baptiste Cope, described as the Chief Sachem of the Mi'kmaq inhabiting the eastern part of Nova Scotia, and Governor Hopson of Nova Scotia, made peace and promised hunting, fishing, and trading rights. |

|

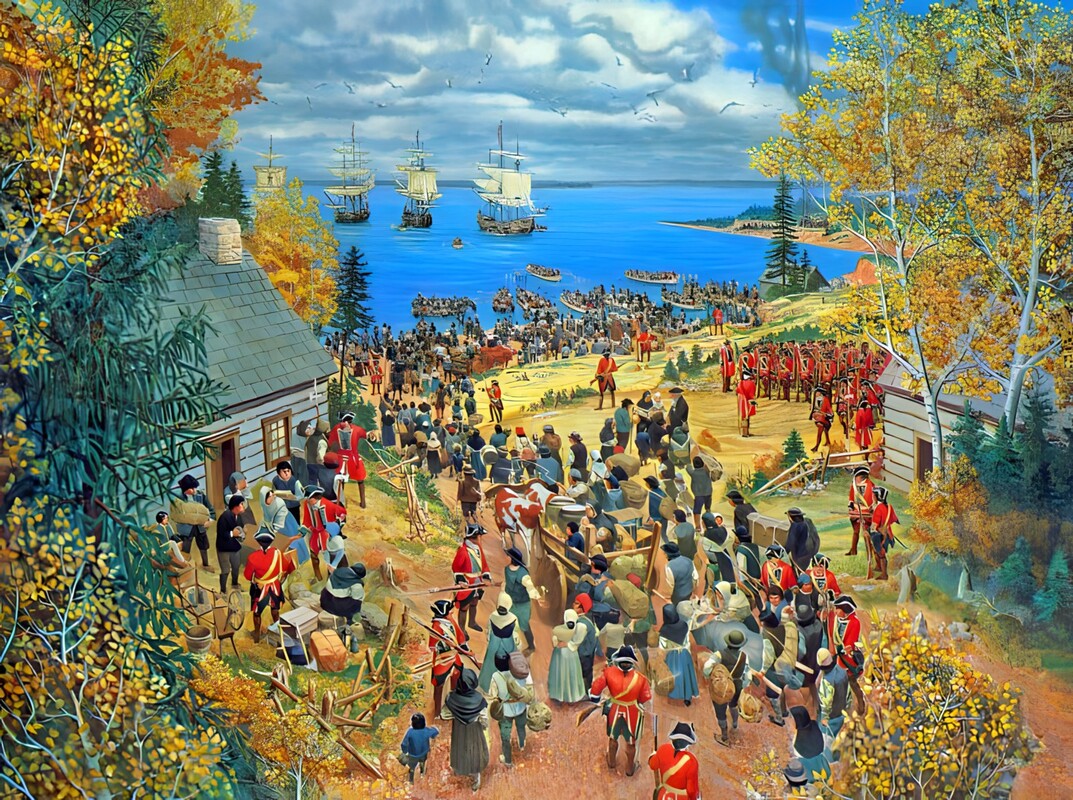

The Deportation of the Acadians scarred the landscape. In 1755, the New England and British troops burned many Acadian houses, barns, churches and other structures as they depopulated the areas. They wanted to make sure that no shelter was left behind for anyone who escaped Deportation. In the overall Minas Basin area, soldiers set fire to about 700 houses, barns, and other buildings. Colonel John Winslow was on horseback while the British Soldiers are forcing the Acadians to the Shore of Minas Basin known as Horton's Landing, from where they were deported on the arriving ships. |

In 1755, the removal of the roughly 2100 people who lived at Grand Pré proceeded neither quickly nor smoothly. Winslow had to cope with a shortage of transport ships and provisions. The men and boys spent more than a month imprisoned within either the church of Saint-Charles-des-Mines or on the transports anchored in the Minas Basin before the rest of the population was forced on board the ships. This 1748 map shows plans to settle Protestants at Grand Pré, prior to the Acadian Deportation in 1755. The British authorities had planned settlements (shown as grids on this map) in the immediate vicinity of the existing Acadian settlements (illustrated as concentrations of houses here). Note, the large concentration of houses and the church (shown as a square with a cross) at Grand Pré, in the middle of the map, illustrating the importance of the settlement of Grand Pré. |

|

|

New England Planters |

|

Beginning in 1760, New England Planters settled at Grand Pré and re-established agriculture on the dykelands. The Planters adopted the dykeland technology of the Acadians and eventually expanded the dyked area by some twenty percent to its current size of 1,300 hectares (over 3000 acres).

|

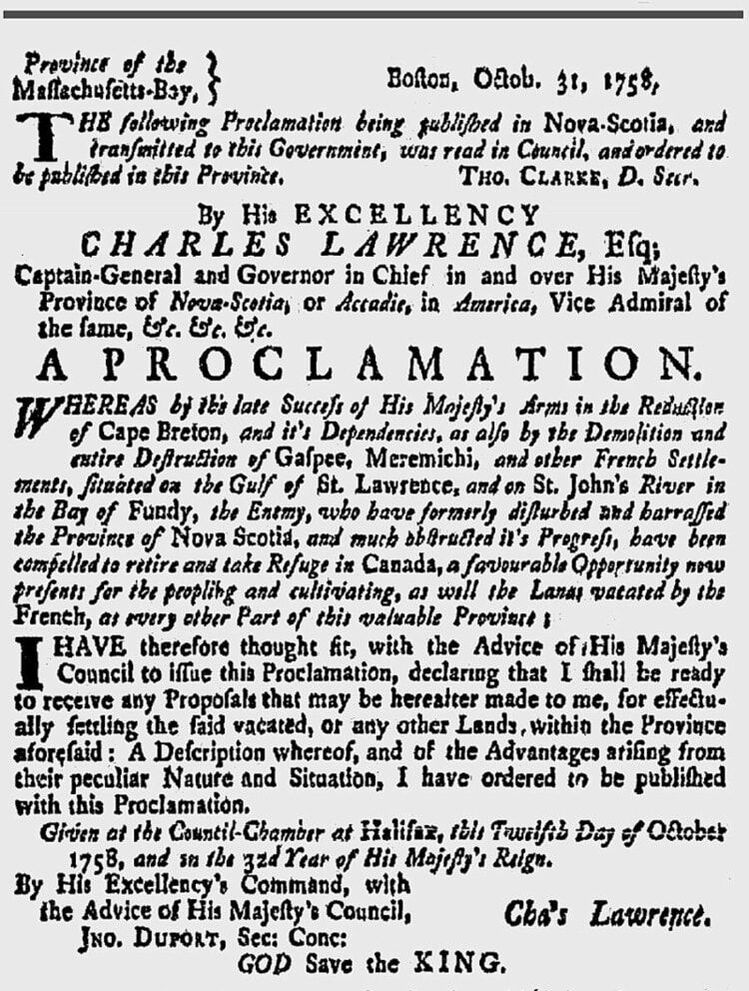

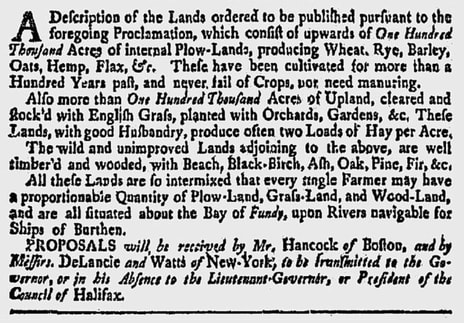

In 1760, five years after the Acadians were first deported from Grand Pré and dispersed throughout the world, a contingent of New England Planters arrived to settle in the transformed marsh land of Grand Pré. The highly fertile land was the most influential reason for this emigration from New England, the primary incentive to move to Nova Scotia was the 1758 Proclamation by General Charles Lawrence that every head of family was entitled to one hundred acres of wild land and another fifty acres for each member of his household, up to one thousand acres. The land would be free of charge for ten years, after which a small rent would be charged.

Collective management of the dykeland by the Planters began in 1761 with the appointment of a Commissioner of Sewers. Today, the dykeland owners, many of whom are Planter descendants, and Dutch farmers who settled in Canada after the Second World War are members of the Grand Pre Marsh Body, the organization of landowners created in 1949 to protect and maintain the dykelands for agricultural purposes.

|

|

|

Birth of an Acadian Symbol |

|

Grand-Pré is more strongly identified with the Deportation than any other site because of the detailed journal kept by Winslow in 1755, and because of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow chose it as the setting of his epic poem Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie published in 1847. The bust of Longfellow commemorates the attention the author brought to the Acadian story. One of Canada's first feature films told the story in 1913.

|

|

Evangéline and Gabriel |

|

Longfellow's poem became a rallying point for the Acadian people following its publication in 1847. The story of a young Acadian girl [Evangeline] from Grand-Pré, separated from her betrothed [Gabriel] during the deportation and her lifetime of searching for him, touched millions of people around the world. Much more than a fictitious character, Evangeline symbolizes the perseverance of the Acadian people.

|

|

Commemorating History |

|

Then, beginning in the late 19th century and continuing until today, Grand Pré developed as the most important place of remembrance of the Acadian people. Memorials and commemorative gardens were created adjacent to the transformed marsh to mark the ancient Acadian settlement, commemorate the removal of the people in 1755, and celebrate the vitality of the Acadian community. In 1917, John Frederic Herbin, built a stone cross on the site to mark the cemetery of the church, using stones from the remains of the Acadian foundations.

|

|

Evangeline |

|

In 1920 the heroine of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem has given her name to many local attractions, including the Evangeline Trail and Evangeline Beach. The Evangeline Statue has welcomed visitors to Grand Pré for more than one hundred years.

|

|

Memorial Church |

|

John Frederic Herbin purchased the site of the church and cemetery of Saint-Charles-des-Mines in 1907 and established Grand-Pré Park as a memorial to the Acadians. he sold the park to the Dominion Atlantic Railway on condition that the church site be deeded to the Acadian people. The railway company assumed responsibility for the park and landscaped the grounds the same year.

Built in 1922, with funds raised from Acadian communities throughout North America, the Memorial Church symbolizes the spirit of Acadian nationalism and the deep-seated desire to commemorate the tragedy of the Deportation.

|

|

Horton Landing Site |

|

Horton Landing commemorates the national significance of the arrival of New England Planters to Grand Pré in 1760. You can see the dykes protecting the fields and the Deportation Cross, originally erected in 1924 as a memorial to the Acadians deported from this spot.

|

|

National Historic Site |

|

Dominion Atlantic sold the land that would become the existing National Historic Site, to the Canadian federal government in 1957. Parks Canada took over operation of the park that was designated a National Historic Site in 1982. The Visitor Reception and Interpretation Centre opened in September 2003 with new interpretation exhibits about the history of Grand-Pré and Acadia.

A video presentation presents the story of the Acadian deportation.

A video presentation presents the story of the Acadian deportation.

|

|

UNESCO Designation |

|

The Landscape of Grand Pré was inscribed on the prestigious UNESCO World Heritage List in 2012, to preserve, protect and promote the remarkable story of the historical link between a landscape and its inhabitants to define a collective identity.

|

|

The View Park |

|

The View Park was established as Annapolis Valley's answer to Peggy's Cove in 2012, after two homes were purchased by Parks Canada to provide an incredible view of the entire landscape of Grand Pré UNESCO wold heritage site. A commemorative solid granite harvest table was added to the site in 2016 to celebrate the `breaking of bread` between the Mi`kmaq, Acadian`s, Planter`s and Canadians who have lived off of the landscape of Grand Pré for the last 400 years.

|

|

Acadian Timeline |

|

1603 Pierre Dugua de Mons is given monopoly of the fur trade in New France, now Nova Scotia, by King Henri IV, and becomes the first governor of Acadie.

1604 De Mons and Samuel de Champlain, along with 77 other men, leave France to sail to New France. During the first winter at the settlement in Île Ste-Croix, a lack of fresh fruit and vegetables leads to an outbreak of scurvy. Of 79 men, 65 fall ill of scurvy; 35 of them die.

1605 De Mons and the remaining men move their settlement to Port-Royal, a location that they hope will have milder winters. It becomes the first permanent settlement in New France.

1632 Although French settlement is continuous, a large number of settlers arrive between 1632 and 1653. Ownership of Acadie is fought over by France and England, and it exchanges hands many times.

1654 Under English rule, French settlement ceases, but it resumes in 1670 following the Treaty of Breda (1667).

1713 The Treaty of Utrecht ends the War of Spanish Succession, making the Acadians in Nova Scotia permanent British subjects. Île Royale (Cape Breton) and Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) remain under French control.

1719 Work begins on the Fortress of Louisbourg to secure France’s stronghold on Île Royale. It becomes one of the busiest ports on the Atlantic coast.

1745 Louisbourg falls to British forces from New England. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle returns Louisbourg to the French in 1748.

1749 The establishment of Halifax engrains a solid British presence in Nova Scotia.

1755 Acadians refuse to sign an oath of allegiance to Britain that would make them loyal to the Crown instead of being “French neutrals.”British Lieutenant Governor Charles Lawrence and the Nova Scotia Council decide on July 28 to deport the Acadians.

The deportation orders are given on August 11, 1755, beginning the Grand Dérangement.

British military begin the deportation process at Fort Beauséjour and order the Acadians’ settlements to be destroyed.

1755-1764 More than 6,000 Acadians are forcibly removed from their homes and deported to Québec, the 13 Anglo-American colonies, as well as Britain, and France. Many are put in jail or die at sea. Others make their way to Québec, hide with the Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia, or travel to present-day New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island.

Between 10,000 and 18,000 Acadians are displaced during le Grand Dérangement, and thousands more are killed. Many families who are separated during this period are never reunited.

1763 The Treaty of Paris grants Great Britain colonial possession of North America, except the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon, off the coast of Newfoundland.

1764 British authorities allow Acadians to return in small isolated groups. They return slowly, settling in various locations in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. Others end up in Newfoundland, the West Indies, and even the Falkland Islands.

1765-1785 About 3,000 deported Acadians travel from France to settle in Louisiana, which had become a colony of Spain in 1763. Their descendents, the Cajuns, maintained the culture and language to some degree.

1836 Simon d’Entremont is the first Acadian to be sworn in as a member of the Legislative Assembly of Nova Scotia.

1847 The American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem Évangéline is published, based on the events surrounding the Deportation of 1755. The title character becomes a folklore heroine.

1864 St. Joseph’s College is founded in Memramcook, N.B.; it is the first higher educational institution in Acadie.

1867 Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, and Québec are united together by the British North America Act, becoming the Dominion of Canada.

1881 The first Acadian convention establishes August 15 as National Acadian Day.

1884 An Acadian flag and a national anthem are adopted at the second Acadian convention.

1890 Collège Ste-Anne, today called Université Sainte-Anne, is established in Pointe-de-l’Église (Church Point), NS.

1923 Peter J. Veniot became the first Acadian Premier of New Brunswick.

1960 Louis J Robichaud is the first Acadian to lead his party to an election victory, serving as Premier of New Brunswick until 1970.

1963 The Université de Moncton is founded and becomes the largest francophone institution of higher education outside Québec.

1994 The first Congrès mondial acadien is held in southeastern New Brunswick.

1996 The creation of a French-language school board, the Conseil scolaire acadien provincial, provides the Acadian and francophone students of Nova Scotia with French first language education from primary to grade 12.

1999 The Congrès mondial acadien is held in the Acadiana region, Louisiana.

2003 A proclamation, issued in the name of the Queen by the Governor General in 2003, recognizes the wrongs suffered by the Acadians during the Grand Dérangement (Deportation). July 28 was set aside as a day to commemorate the Great Upheaval, beginning in 2005, the 250th anniversary of the Grand Dérangement.

2004 The Congrès mondial acadien is held in Nova Scotia. The year 2004 marks the 400th anniversary of continuous French settlement in North America, and it is proclaimed l’Année de l’Acadie in Nova Scotia.

2005 This year marks the 250th anniversary of the Grand Dérangement.

2009 Congrès mondial acadien is held in the Acadian Peninsula of New Brunswick.

2012 The Landscape of Grand-Pré is declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Source: https://acadien.novascotia.ca/en/timeline