The dykelands, fields, and settlement on the hills, first established by the Acadians in the 1680s, have been maintained and expanded over centuries by farmers of New England Planter descent, and later immigrants - including English and Scottish who came in the 19th and 20th centuries and Dutch who arrived after the Second World War.

|

|

|

Protecting Communities and

|

|

|

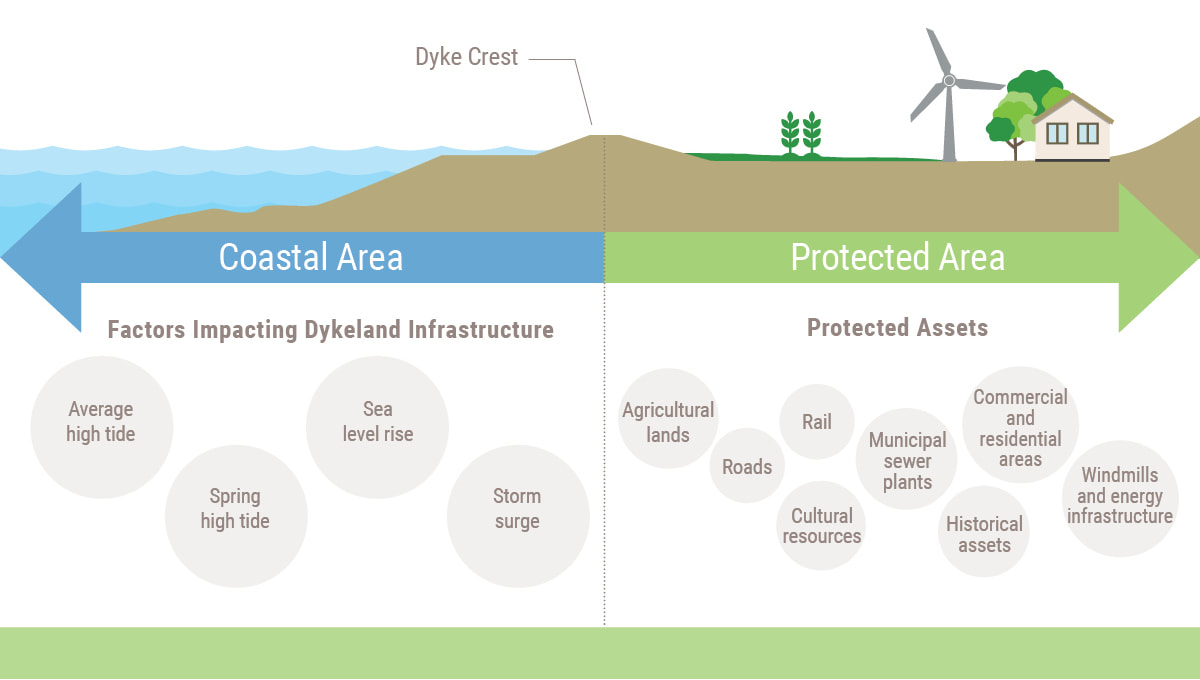

Nova Scotia’s dykeland system protects agricultural land, public infrastructure, cultural assets and commercial and residential properties throughout the province. The system needs to be upgraded to reduce the potential economic, environmental and social effects of climate change as storms increase in intensity and frequency.

|

|

Natural Fertility |

|

By any measure, the Bay of Fundy is an extraordinary, complex and highly productive ecosystem. All coastal waters and estuaries tend to be biologically rich because they are adjacent to land that provides a steady supply of nutrients, are generally shallow so that light and nutrients are available to support plant growth, and provide a diverse array of habitats for different species.

In the Bay of Fundy, these natural attributes are enhanced by the dramatic tides. Tides create major upwelling areas at the mouth of the Bay in which cold, nutrient-rich water is brought to the surface where light is available to support growth of phytoplankton. This is the foundation for a highly productive food chain that sustains vast numbers of animals from plankton to whales. This is also one of the major reasons that numerous species of fish, birds and mammals migrate to the Bay of Fundy to feed each year.

At the head of the Bay, in the Minas Basin, the larger tides drive a totally different ecosystem, one in which the waters are cloudy because of silts and clays kept in suspension by the tides. There is little biological production in the water, but at the same time large areas of intertidal zone are exposed where phytoplankton and salt marshes flourish. Sustained both by the constant provision of sediment and by the continuous supply of nutrients brought in on the rising tide, salt marshes are more extensive in the Minas Basin, allowing the marsh to grow as sea level rises. As a result, the Fundy marshes are naturally among the richest in the Northern Hemisphere. Together, the marshes and mudflats provide a major feeding ground that attracts millions of fish and birds.

At the head of the Bay, in the Minas Basin, the larger tides drive a totally different ecosystem, one in which the waters are cloudy because of silts and clays kept in suspension by the tides. There is little biological production in the water, but at the same time large areas of intertidal zone are exposed where phytoplankton and salt marshes flourish. Sustained both by the constant provision of sediment and by the continuous supply of nutrients brought in on the rising tide, salt marshes are more extensive in the Minas Basin, allowing the marsh to grow as sea level rises. As a result, the Fundy marshes are naturally among the richest in the Northern Hemisphere. Together, the marshes and mudflats provide a major feeding ground that attracts millions of fish and birds.

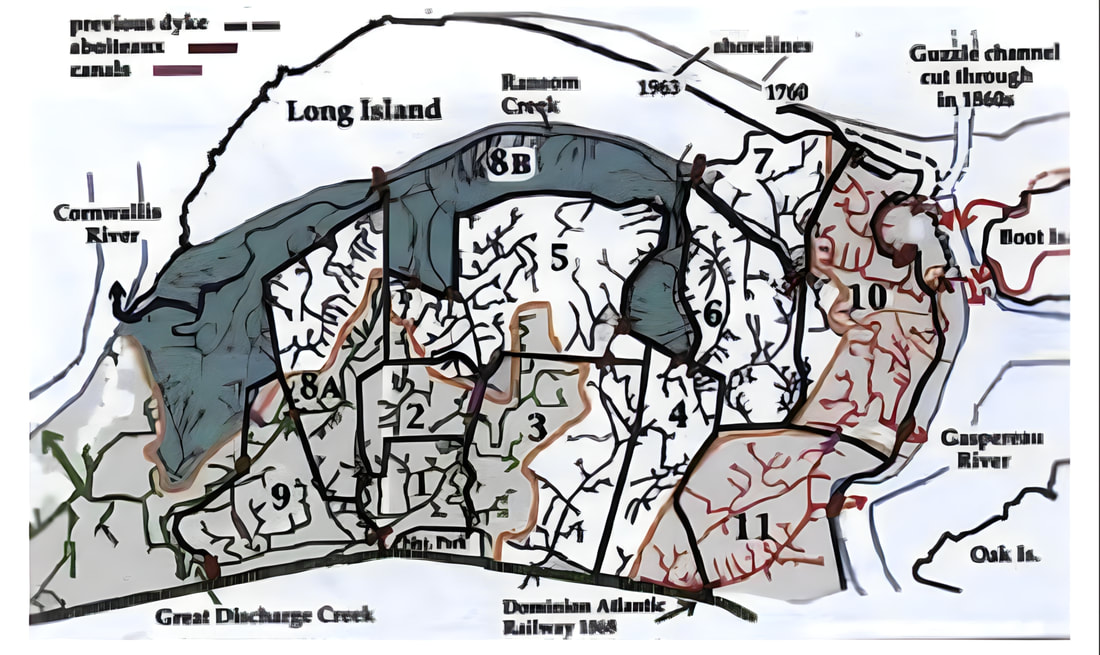

Biologist and historian Sherman Bleakney's map of the Grand Pré dykelands indicates the sequence of dyking.

For much of the 4000 years that the Minas Basin has been tidal, salt marshes have been present, building up continuously to keep pace with sea level rise. This vertical increase results from the trapping of sediments, together with absorbed nutrients, by salt marsh plants as the tide rises twice each day. Thus a Fundy salt marsh represents thousands of years of biological production: the plant roots, sediments and nutrients have been stored in the marsh over a geological timespan, producing an accumulation of fertile soil. With the coming of the Acadians, and the dyking of some of these marshes, that fertility became available for agriculture. Indeed, topsoil is on average four and a half metres deep. Although the low permeability of the sediment makes it difficult for salt to be washed out of the soil, farmers were still able to grow shallow-rooted crops. Prior to the Acadian settlement, human use of the Bay of Fundy was mainly through the capture of animal life – shellfish, fish, birds and mammals.

|

|

The Highest Tides in the World |

|

The greatest ranges and the greatest extent of an intertidal zone occur today in the Minas Basin. As part of the tidal cycle – two high tides and two low tides daily–100 billion tonnes of sea water flow in and out of the Minas Basin twice each day. That is more water than the combined daily flow of all the world’s rivers.

Following the retreat of the glaciers after the last Ice Age about 14 000 years ago, sea levels around the planet rose. Rivers draining from the newly deglaciated land began to wash away sediment. In Eastern Canada, these sediments came to line the bottom of the Bay of Fundy. At this time, the Minas Basin was a shallow freshwater or brackish lake, and Georges and Browns Banks at the entrance to the Bay of Fundy were dry land. As sea levels continued to rise, and Georges Bank became submerged, more sea water entered the Bay. By 4000 years ago, the tidal range in the Minas Basin was only about 1 to 1.5 metres (3.2–4.9 feet), but this range has steadily increased over time to an average of 12 metres (39 feet) in the Minas Basin, 11.61 metres (38 feet) at Grand Pré and a maximum in excess of 16 metres (52.5 feet) – the highest recorded tides in the world.

|

|

Dykeland Creation 1680–1755 |

|

The Acadians’ focus and ability to transform marshes is distinctive in colonial North America. They were the only pioneer settlers in that era to farm so extensively below sea level. The first recorded evidence of dykelands comes from the Port Royal area at the site of the first successful permanent French settlement in North America

|

|

Dykeland Expansion 1806–1907 |

|

The first expansion of the dykeland occurred in 1806 on the west side, with the building of the “New Dike” or “Wickwire Dyke”.

It was built west of the north–south Acadian dyke in an area the Acadians had never dyked, in part because of the challenges of resisting the tidal pressure. This dyke enclosed over a hundred hectares of new farmland and withstood the brunt of storms and tides coming from the west. It did not break until 1869, when the Saxby Gale lashed the coast, bringing a combination of high tides and strong winds. As the Acadian dykes had been left in place after the Wickwire Dyke was built, the main Grand Pré Marsh remained relatively untouched. The Wickwire Dyke was rebuilt in 1871. The maintenance and expansion of the dykes allowed farmers to maintain a high level of productivity that was admired by experts and visitors. The foremost Nova Scotian expert on agriculture in the early 19th century, John Young, offered an assessment of the Grand Pré dykeland in 1822. At that point, the dykelands had been in New England Planter hands for about 60 years:

|

The coast of the Bay of Fundy is unquestionably the garden of Acadia, and accordingly we find that the French planted themselves there on the first occupation of the country. They threw across those dikes and aboiteaux by which to shut out the ocean, that they might possess themselves of the rich marshes of Cornwallis and Horton, which prior to our seizure they had cropped for a century without the aid of manuring. … Spots in the Grand Prairies [Grand Pré] of Horton have been under wheat and grass alternately for more than a century past, and have not been replenished during that long period with any sort of manure.

|

|

Writing in the early 1880s, another expert, D.L. Boardman, observed;

[The] Grand Pré Dike [dykeland] is one of the oldest in Kings County and one of the best in the province. The old French had dikes here on the first occupation of the country, and there are now to be seen all over the Grand Pré remains of old dikes within those now doing their duty in keeping back the tide. These have been plowed down and leveled off in places, but it is not a difficult matter to trace them.

|

The American biologist and writer Margaret W. Morley (1858–1923) was clearly impressed by what the Acadians had first achieved and the New England Planters maintained when she wrote in 1905: “[We] cannot gaze upon the broad meadows before the door of Grand Pré without remembering the hands that first held back the sea.”

|

|

Dyke and Aboiteau Maintenance at Grand Pré |

|

This strong symbolic landscape has remained a strong agricultural landscape. The dykes at Grand Pré are maintained, and new expansions have been partially built as well on the west side. The northeastern dyke on Long Island and parts of the eastern dykes were built in the 1940s, some behind the previous lines of dykes, others in front. The Wickwire Dyke, rebuilt in the 19th century, was again abandoned in 1932 following years of degradation from violent storms. It was rebuilt for a second time in 1959. The footprints of sections of other dykes were moved to maintain their ability to withstand the tides. In each case, the decision to build dykes was based on the capacity to maintain the integrity of the system of dykes and aboiteaux.

The dykes built in the 1940s, along with the rebuilding of the Wickwire Dyke, were part of a government initiative known as the Emergency Programme. In 1943, the federal government and the provincial governments of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick established the Maritime Dykeland Rehabilitation Committee (see Figure 2–52).

An even more ambitious initiative followed in 1948, with the creation of the Maritime Dykeland Rehabilitation Administration through an act of the Parliament of Canada. The task of maintaining the condition of all dykelands in the maritime provinces was thus treated as a single project that unlocked major financial resources. By the late 1960s, all major projects of rebuilding dykes and replacing aboiteaux had been completed. Supervision of the dyke maintenance was transferred to the provinces, where the responsibility remains to this day.

Throughout three centuries of evolution and changes, Grand Pré farmers have retained their distinctive approach to building and maintaining the original dykeland. The design of aboiteaux has not changed, although new materials now enhance their reliability and lifespan. The dykes are still built from earth, and the native vegetation continues to protect them. For 300 years, local farmers have experimented with different combinations of materials to strengthen the dykes – sometimes using rocks, sometimes wooden planks held with rods as facing (known as a “deadman”) – yet the basic technology is the same. The creeks have been kept intact to ensure the proper drainage patterns.

Today’s farmers, some of New England Planter descent and many of Dutch origin who arrived after the Second World War, continue to retain the knowledge of dyke building and maintenance. While few local farmers still know how to handle a spade to cut sod into bricks, many understand the appropriate design and the inner workings of drainage and of aboiteaux, as evidenced by the private dykes and aboiteaux that continue to be built. The Department of Agriculture has some of this knowledge, but it needs the experience of the farmers to maintain the dykes.

Community-based management continues today in the 21st century. The farmers of the Grand Pré Marsh Body own the land individually but share resources and make decisions collectively about maintaining the marsh. The farmers do not have direct responsibility for the dykes but retain an essential role in their maintenance and the experience of building them. Their management approach keeps alive the spirit of collective concern for this agricultural landscape and the individual desire to thrive. Throughout the major federal and provincial government projects of the past 70 years, the Grand Pré Marsh Body maintained its role. The Grand Pré Marsh Body’s recorded minutes and archives go back to the late 18th century. It is the oldest and most active organization of its type in North America.

The dykes built in the 1940s, along with the rebuilding of the Wickwire Dyke, were part of a government initiative known as the Emergency Programme. In 1943, the federal government and the provincial governments of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick established the Maritime Dykeland Rehabilitation Committee (see Figure 2–52).

An even more ambitious initiative followed in 1948, with the creation of the Maritime Dykeland Rehabilitation Administration through an act of the Parliament of Canada. The task of maintaining the condition of all dykelands in the maritime provinces was thus treated as a single project that unlocked major financial resources. By the late 1960s, all major projects of rebuilding dykes and replacing aboiteaux had been completed. Supervision of the dyke maintenance was transferred to the provinces, where the responsibility remains to this day.

Throughout three centuries of evolution and changes, Grand Pré farmers have retained their distinctive approach to building and maintaining the original dykeland. The design of aboiteaux has not changed, although new materials now enhance their reliability and lifespan. The dykes are still built from earth, and the native vegetation continues to protect them. For 300 years, local farmers have experimented with different combinations of materials to strengthen the dykes – sometimes using rocks, sometimes wooden planks held with rods as facing (known as a “deadman”) – yet the basic technology is the same. The creeks have been kept intact to ensure the proper drainage patterns.

Today’s farmers, some of New England Planter descent and many of Dutch origin who arrived after the Second World War, continue to retain the knowledge of dyke building and maintenance. While few local farmers still know how to handle a spade to cut sod into bricks, many understand the appropriate design and the inner workings of drainage and of aboiteaux, as evidenced by the private dykes and aboiteaux that continue to be built. The Department of Agriculture has some of this knowledge, but it needs the experience of the farmers to maintain the dykes.

Community-based management continues today in the 21st century. The farmers of the Grand Pré Marsh Body own the land individually but share resources and make decisions collectively about maintaining the marsh. The farmers do not have direct responsibility for the dykes but retain an essential role in their maintenance and the experience of building them. Their management approach keeps alive the spirit of collective concern for this agricultural landscape and the individual desire to thrive. Throughout the major federal and provincial government projects of the past 70 years, the Grand Pré Marsh Body maintained its role. The Grand Pré Marsh Body’s recorded minutes and archives go back to the late 18th century. It is the oldest and most active organization of its type in North America.