Here at Grand Pré, as elsewhere in Acadie, the Acadians established their settlements to take advantage of the potentially fertile salt marshes. In fact, no other people in North America developed agricultural communities as extensively as the Acadians did by transforming intertidal zones with the use of aboiteau technology

|

|

Agricultural Excellence |

|

|

|

A Natural Fertility |

|

By any measure, the Bay of Fundy is an extraordinary, complex and highly productive ecosystem. All coastal waters and estuaries tend to be biologically rich because they are adjacent to land that provides a steady supply of nutrients, are generally shallow so that light and nutrients are available to support plant growth, and provide a diverse array of habitats for different species.

In the Bay of Fundy, these natural attributes are enhanced by the dramatic tides. Tides create major upwelling areas at the mouth of the Bay in which cold, nutrient-rich water is brought to the surface where light is available to support growth of phytoplankton. This is the foundation for a highly productive food chain that sustains vast numbers of animals from plankton to whales. This is also one of the major reasons that numerous species of fish, birds and mammals migrate to the Bay of Fundy to feed each year.

At the head of the Bay, in the Minas Basin, the larger tides drive a totally different ecosystem, one in which the waters are cloudy because of silts and clays kept in suspension by the tides. There is little biological production in the water, but at the same time large areas of intertidal zone are exposed where phytoplankton and salt marshes flourish. Sustained both by the constant provision of sediment and by the continuous supply of nutrients brought in on the rising tide, salt marshes are more extensive in the Minas Basin, allowing the marsh to grow as sea level rises. As a result, the Fundy marshes are naturally among the richest in the Northern Hemisphere. Together, the marshes and mudflats provide a major feeding ground that attracts millions of fish and birds.

For much of the 4000 years that the Minas Basin has been tidal, salt marshes have been present, building up continuously to keep pace with sea level rise. This vertical increase results from the trapping of sediments, together with absorbed nutrients, by salt marsh plants as the tide rises twice each day. Thus a Fundy salt marsh represents thousands of years of biological production: the plant roots, sediments and nutrients have been stored in the marsh over a geological timespan, producing an accumulation of fertile soil. With the coming of the Acadians, and the dyking of some of these marshes, that fertility became available for agriculture. Indeed, topsoil is on average four and a half metres deep. Although the low permeability of the sediment makes it difficult for salt to be washed out of the soil, farmers were still able to grow shallow-rooted crops. Prior to the Acadian settlement, human use of the Bay of Fundy was mainly through the capture of animal life – shellfish, fish, birds and mammals.

In the period just before the first Acadians came to settle at Grand Pré, the lower-lying parts of what is today the Grand Pré dykelands were covered twice a day by sea water. The higher areas were covered less frequently, just during extreme high tides. When the tide fell, it revealed an extensive salt marsh, consisting of over 1000 hectares of marsh grasses and tidal drainage creeks. This luxuriant marsh was home to a wide range of marine and estuarine life.

|

|

Salt Marshes to Farmlands |

|

For some 70 years before their forcible removal in 1755, the Acadians living at Grand-Pré collectively transformed the extensive salt marshes into the “grand pré” (the big meadow.) The Acadians used the aboiteau system, a European wetlands technology, which they adapted to the local environment. Once dyked and rainwater had washed out the salt from the rich soil deposited by the Bay of Fundy tides, this area became extremely fertile and was often referred to as the “Breadbasket of Acadie”.

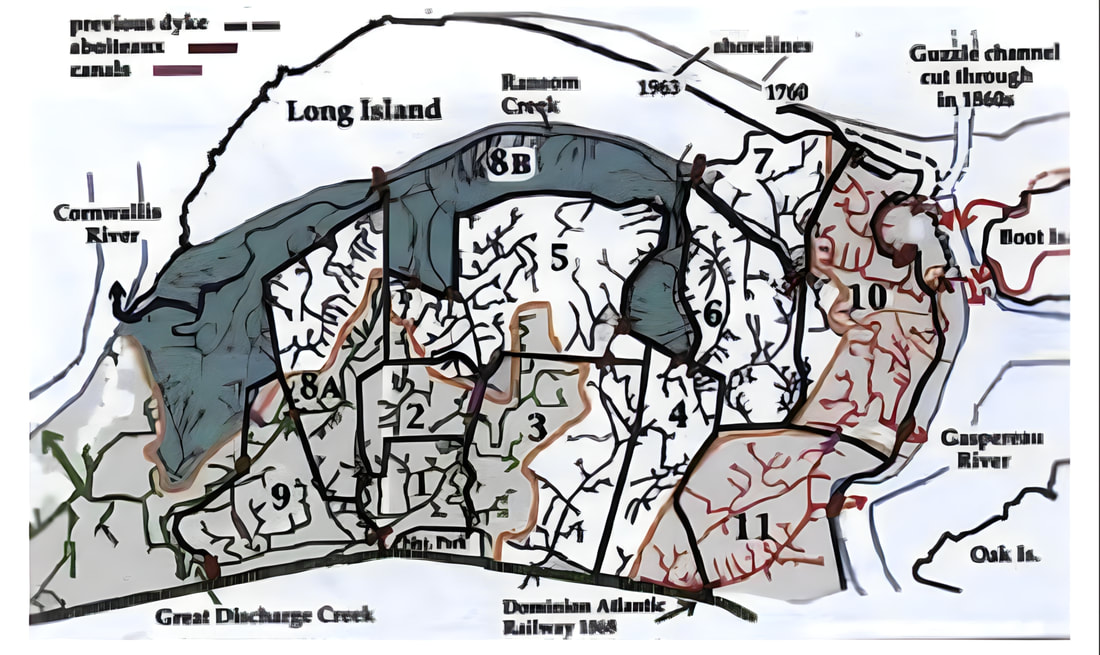

(Figure 2-28) Biologist and historian Sherman Bleakney's map of the Grand Pré dykelands indicates the sequence of dyking.

|

|

Unnatural Landscapes |

|

The film by RONALD RUDIN and BERNAR HÉBERT takes viewers on a journey through 32,000 hectares of marshlands in the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

|

|

Centuries of Progress and Adaptation |

|

Many farmers today raise milk-producing cattle and grow crops for their animals. As milk production is a regulated industry, the farmers have a stable means of ensuring their livelihood.

In the past, dykeland was used for crops during summer and as common pasture in the fall. This allowed nutrients in the form of manure to be reintroduced into the soil. The farmers would gather in Grand Pré next to the dykelands to divide the herds into two, one for the east section and one for the west. They would identify individual branding tools, fence the area, brand the animals, and let them loose on the dykelands. That practice continued until the 1970s, when crops became more sensitive to the impact of cattle and when new farming techniques lengthened the season. Today, cattle are still sent for pasturing on the dykeland, but only in specific areas

Starting in the 1970s, farmers placed an emphasis on the surface drainage of these soils. Their method of drainage became known as landforming and involved shaping the surface of a field so that excess rainfall ran off into grassy ditches (see Figure 2–54).

Starting in the 1970s, farmers placed an emphasis on the surface drainage of these soils. Their method of drainage became known as landforming and involved shaping the surface of a field so that excess rainfall ran off into grassy ditches (see Figure 2–54).

|

Landforming in Grand Pré consists of open ditches with a 30-centimetre drop over a distance of 300 metres to drain into the creeks. As a result, the soil dries much faster and holds the heat more efficiently. Farmers can begin working the land earlier in the season and grow a greater variety of crops. Typical crops are pasture, hay, cereals, soy, alfalfa, and some vegetables. During dry summers, dykeland soils hold water better than the upland soils.

Many farmers today raise milk-producing cattle and grow crops for their animals. As milk production is a regulated industry, the farmers have a stable means of ensuring their livelihood. Most of the crops grown on the dykelands are intended as cattle feed for both local consumption and sale. The farmers of Grand Pré are recognized as being progressive in their techniques, tools, and use of fertilizers as well as protective of their traditions. |

Today, 100 per cent of the dykeland is used for agriculture, and the area retains its point of pride of being one of the most productive agricultural communities in Atlantic Canada. That enduring use is evidence of a successful adaptation to the prevailing environmental conditions and community management. Future success is assured by the farmers continuing to be the stewards of this agricultural landscape, the product of hard labour, pride, and centuries of acquired knowledge.

Today, the dykelands remain some of the most fertile lands available for agriculture in Canada.