Grand-Pré National Historic Site is also the location of an archaeological site sponsored by St. Mary’s University, Parks Canada, and Sociéte Promotion Grand-Pré. Lead by Proffessor Jonathan Fowler.

|

|

Archaeology |

|

|

|

New GPR Evidence

|

|

|

While excavations have been undertaken by Parks Canada since 1971, the field school has been operational for ten years, during which archaeologists have identified the cemetery for the Acadian period, the cellar of an Acadian house immediately to the east of the Memorial Church, and has conducted test pits throughout the site looking for evidence of the parish church, St-Charles-des-Mines; Pierre-Alain Bugeauld (Bujold) was the Church Warden [Marguillier aux Mines]; was also a Notary (1706) and a Judge/Justice (1707). Acadian artifacts that have been unearthed include fragments of Saintonge ceramic, nails, wine bottle glass, window pane glass, a 1711 French silver coin, spoons, belt buckles, buttons, clay pipes, etc. There seems to also be evidence of the occupation by New England troops, as well as considerable evidence of the New England Planter occupation period beginning in 1760. |

Between 2017 and 2019, we conducted over 40 ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys at Grand-Pré National Historic Site in an effort to map archaeological features associated with the pre-Deportation Acadian settlement at the site.

Mapping the cemetery belonging to the parish church of St-Charles-des-Mines at Grand-Pré was a major focus of the research. Those results are discussed here in a conversation with Professor Jonathan Fowler and the CBC's Portia Clark, recorded on November 13, 2020. |

|

|

The Acadian Cemetery at

|

|

|

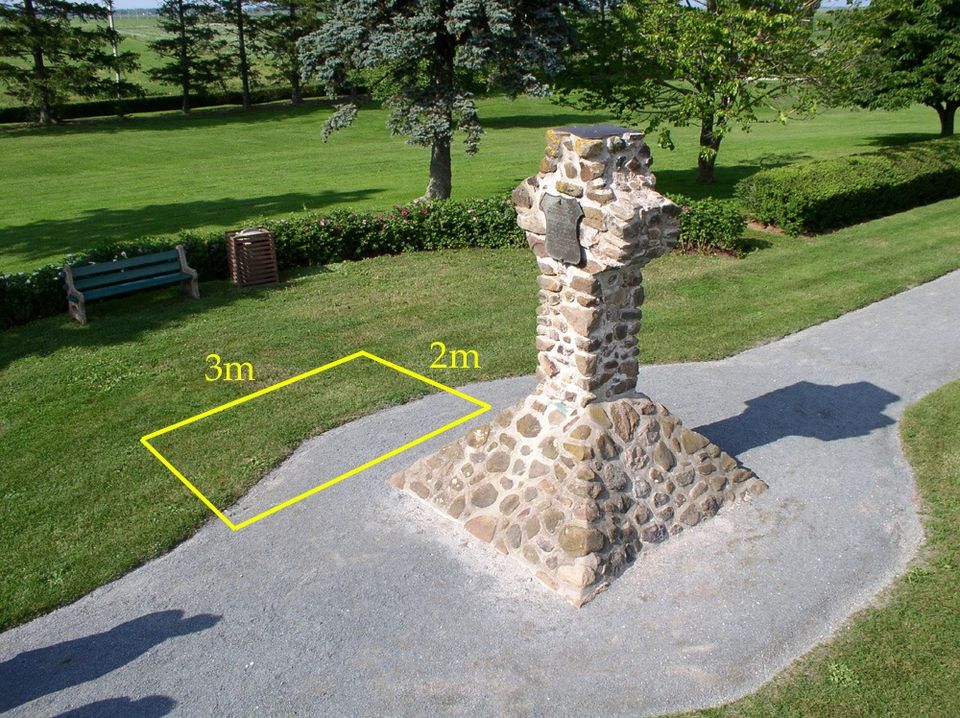

Modern archaeology reached the old cemetery at Grand-Pré National Historic Site 1982. John Herbin’s stone cross, built around 1909 to memorialize the cemetery, had by now weathered over 70 years of fogs, frosts, and blazing heat, and needed repair. This required digging, and Parks Canada archaeologists were eager to get out in front of the project to see if there really were burials nearby. If there were, steps could be taken to mitigate any negative impacts to the graves.

There are several ways to detect unmarked burials. As we’ll see shortly, geophysical methods – especially radar – can be very effective so long as the geology cooperates. Dogs offer a different kind of remote sensing: they can smell human remains, even if those remains are skeletonized and buried. Dogs are often used in forensic cases, but they sometimes assist archaeologists as well. Seeing is believing, though, which is why careful manual excavation of suspected graves ultimately yields the most trustworthy results. This is the method Anita Campbell’s team employed at Grand-Pré in August 1982.

|

They began by opening a 1m x 2m (roughly 3.3’ x 6.6’) excavation unit north of Herbin’s Cross. At a depth of approximately 90cm (3’), the east end of a coffin stain, observable as a line of decayed wood, was revealed. A decision was made to expand the excavation a further 2m (6.6’) in this direction to reveal the entire grave. In the process, parts of three additional graves were revealed in the vicinity. The burials appear to have been closely spaced here and, as expected, aligned east-west.

Preservation was not very good and no human remains were recovered. Only that faint outline of a decayed wooden coffin could be traced, along which hand-forged, rose-headed nails were recovered. Those that had fastened the bottom of the coffin to the side panels were still pointing upward, signifying that this burial was undisturbed by Victorian treasure hunters.

|

|

Clearly, the oral tradition identifying this place as a cemetery was valid, and the evidence presented in the previous two posts convincingly associate it with the Acadian parish church of St-Charles-des-Mines. But how large was this cemetery and where were its boundaries?

These questions were not at the top of our list when we launched our archaeological investigations at Grand-Pré National Historic Site in the summer of 2000. Our principal objective in those days was the old church itself, which was then thought to have stood somewhere around (or beneath) the memorial church Clearly, the oral tradition identifying this place as a cemetery was valid, and the evidence presented in the previous two posts convincingly associate it with the Acadian parish church of St-Charles-des-Mines. But how large was this cemetery and where were its boundaries?

|

|

These questions were not at the top of our list when we launched our archaeological investigations at Grand-Pré National Historic Site in the summer of 2000. Our principal objective in those days was the old church itself, which was then thought to have stood somewhere around (or beneath) the memorial church.

Gradually, though, as we became better acquainted with Grand-Pré's interlocking archaeological mysteries, it dawned on us that defining the cemetery’s boundaries would anchor an important part of the site’s historical geography.

In 1755, the New England military force that occupied Grand-Pré commandeered the church and two nearby houses, and Lieut.-Col. John Winslow ordered a palisade line constructed around these three buildings. The work took the better part of a week and would have required a thousand or more trees to be cut, trimmed, and hauled to the site (by this time in Grand-Pré’s history, the “forest primeval” had been chased up to the neighbouring hilltops by the inhabitants’ tireless axes). Once delivered, the men would have set them vertically into a narrow socket trench dug around the camp’s perimeter, finishing the job by bracing the wall and fixing front and rear gates.

Winslow was a popular commander, but even his men may have grumbled when, a few days after the fort’s completion, they were ordered back to work. The camp was now enlarged to include the cemetery as well as the previously enclosed church, the priest’s house, and another small house. From an archaeological perspective, then, from a starting point within the cemetery, it should be possible to carefully work outward to the line of the enclosing palisade. Once the palisade line is met, it may be followed, drawing a line around the site’s most important archaeological features.

|

Our investigations of the cemetery began with non-intrusive measures, specifically, geophysics. Working with my friend and colleague Duncan McNeill, we employed electromagnetic induction an magnetometry to detect changes in soil conductivity and magnetism that might signify the presence of graves. Sadly, the data were inconclusive, and we were thrown back for a time on traditional methods.

|

This basically involved peeling back the sod and trowelling down to expose subsoil, which in this area has an orange tint and contains more sand and clay than the darker and more loosely compacted topsoil. Features cut into the subsoil and filled with mixed sediments (graves, for instance) can generally be mapped with this method, which is more time-consuming than geophysical but essentially as non-intrusive. We did not excavate into any of the graves we encountered, nor did we discover any human remains. Instead, we mapped the grave shafts and moved on, all the while edging toward the cemetery’s boundaries.

Even working with the most dedicated young archaeologists, this innocent endeavour was a labour of years. Our field schools are offered annually, but only for a few weeks each season, and with teams often exploring multiple sites. And, of course, the weather doesn’t always co-operate. Who can forget the monsoon season of 201

|

|

That method appeared in 2017 with the purchase of our first ground-penetrating radar (GPR), a Noggin 500 manufactured by Sensors and Software, a Canadian firm based in Mississauga, Ontario. Between fall 2017 and spring 2019, we conducted over 40 GPR surveys at Grand-Pré National Historic Site and the results bring the landscape of 1755 into much sharper focus.

Gradually, however, a picture began to emerge, and in 2014 we uncovered what appears to be not only the cemetery’s eastern boundary (a thin fence line), but also – just a few feet beyond – a heavier trench that may well be the socket for John Winslow’s 1755 palisade. But this was slow-going. If only we had a method to map the graves more efficiently…

|