In the period just before the first Acadians came to settle at Grand Pré, the lower-lying parts of what is today the Grand Pré dykelands were covered twice a day by sea water. The higher areas were covered less frequently, just during extreme high tides. When the tide fell, it revealed an extensive salt marsh, consisting of over 1000 hectares of marsh grasses and tidal drainage creeks. This luxuriant marsh was home to a wide range of marine and estuarine life.

|

|

1680 -1755

|

|

|

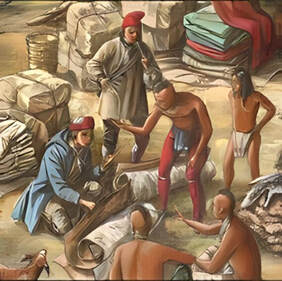

Acadian settlers maintained positive relations with the Mi’kmaq throughout the late 17th and early 18th centuries, which were years of political uncertainty. As the French and British imperial powers fought for control of Nova Scotia, the settlers were left to build their own alliances and trade networks. The physical transformation of the landscape could only have taken place with the acceptance of the Mi’kmaq, since the latter greatly outnumbered the Acadians in that area in the late 17th century. An analysis of the Acadian parish records between 1707 and 1748 reveals a high number of mixed heritage individuals at Grand Pré. Of the many different Acadian communities before 1755, Grand Pré was the one with the highest percentage of mixed heritage families. There are also frequent documentary references to the Mi’kmaq being at or near Grand Pré, in what the Acadians called the district of Les Mines |

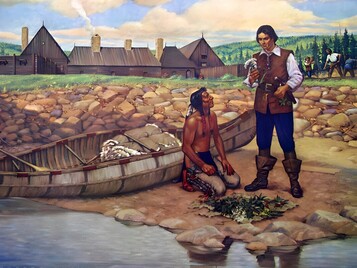

When the first Europeans arrived in the 17th century to the area that is now Nova Scotia, they found willing trading partners in the Mi’kmaq, who had developed sophisticated trading networks over the millennia. During the succeeding centuries, European settlements gradually encroached on Mi’kmaq territory, especially the rich coastline, and intense competition for the region’s resources ensued. Early on, though, the French authorities and the Mi’kmaq forged positive relationships that led to alliances. One such alliance resulted from the historic baptism of Grand Chief Henri Membertou in 1610, the first Aboriginal person to be baptized in what would later become Canada. There are no known treaties between the French and the Mi’kmaq.

|

|

|

Creation of the Dykeland

|

|

When the Acadians began transforming the marsh at Grand Pré, the Mi’kmaq did not prevent them from altering and ultimately removing a vast wetland from the regional resource base. This attests to the harmonious relationship that generally existed between the two peoples, a relationship that was rare in colonial era North America

|

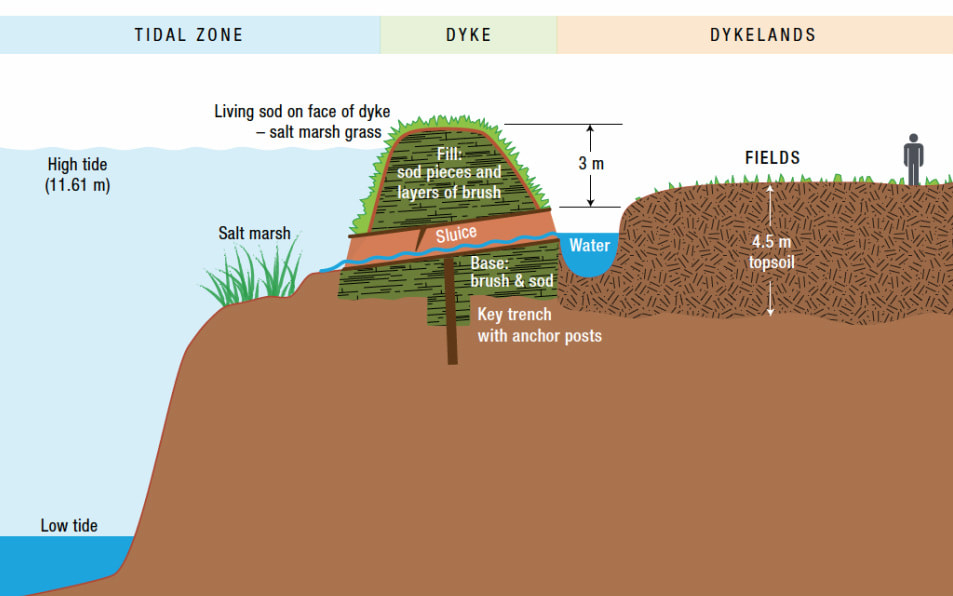

For much of the 4000 years that the Minas Basin has been tidal, salt marshes have been present, building up continuously to keep pace with sea level rise. This vertical increase results from the trapping of sediments, together with absorbed nutrients, by salt marsh plants as the tide rises twice each day. Thus a Fundy salt marsh represents thousands of years of biological production: the plant roots, sediments and nutrients have been stored in the marsh over a geological timespan, producing an accumulation of fertile soil. With the coming of the Acadians, and the dyking of some of these marshes, that fertility became available for agriculture. Indeed, topsoil is on average four and a half metres deep. Although the low permeability of the sediment makes it difficult for salt to be washed out of the soil, farmers were still able to grow shallow-rooted crops. Prior to the Acadian settlement, human use of the Bay of Fundy was mainly through the capture of animal life – shellfish, fish, birds and mammals.

|

|

|

The French in Acadie |

|

The Acadians are a people born in North America. Their identity is the result of the transformation of their individual European values as they came into contact with a new environment and new people. Their story begins with the French settlement of North America.

In 1604, the French made their first attempt to establish a permanent settlement in North America, at Ile Sainte Croix in the Bay of Fundy. They were quickly demoralized and threatened by the rigours of winter in this climate. In 1605, they tried again, better prepared and better located at Port Royal in today’s southwestern Nova Scotia. That settlement succeeded, signalling the foundation of a territory called Acadie which the French claimed included roughly the lands between the 40th and 60th parallels along the Atlantic Ocean. This would cover today’s Canadian provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, plus eastern Québec and parts of three American states in New England.

|

Transitioning from French to Acadian came gradually as a result of the social, environmental, and political influences. The settlers found themselves in a wholly unfamiliar environment and having to adapt to a new climate, wildlife, and vegetation. Socially, they were shaped by their contact with the Mi’kmaq, the indigenous people of Nova Scotia.

|

Through the mutual trust and relative harmony that the two peoples established, the French were able to settle peacefully and learn the ways of the land to survive and thrive. The high number of mixed marriages confirms the good relations and strengthened the bond between the two peoples. Politically, since Acadie was strategically important for the imperial powers and changed hands frequently between the British and the French, the settlers were often left to fend for themselves.

Consequently, they took matters of justice, administration, and community life into their own hands. These three environmental, social and political influences greatly affected the settlers’ sense of independence, initiative, and ownership of the land. By the mid-17th century, these characteristics were distinctive enough to have French officials take note and refer to the French settlers as Acadians. As for the British, they referred to them as “French Neutrals,” after the 1730s, as a result of their resolve to remain neutral in the conflicts between France and Britain

|

|

A Disputed Territory |

|

While the French claimed Acadie as their own, the British were competing with them for territorial claims over similar areas. Located strategically between New England to the south and New France to the west, Acadie from the early 1600s onward was often a battleground for control of key settlements and military positions. There were numerous violent incidents and, occasionally, outright wars.

The struggles were sometimes between French and Anglo-Americans, sometimes among rival groups of French colonists, sometimes between French and British forces, and sometimes between the Mi’kmaq and British or Anglo-American forces. All skirmishes, battles, and raids during the 17th and 18th centuries occurred in the broader context of European conflicts resulting from the race to colonize new worlds, dominate lucrative trading routes, and expand empires in Europe and abroad.

The conflicts resulted in the colony of Acadie changing hands frequently. It was under French authority six times and British authority (which, after 1621, sometimes referred to the land as Nova Scotia) four times over 155 years until the French lost Canada in 1763. During that era, Acadians were actively establishing their communities along the Bay of Fundy, the Atlantic Coast, Ile Royale (now Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia), and Ile Saint-Jean (now the province of Prince Edward Island).

|

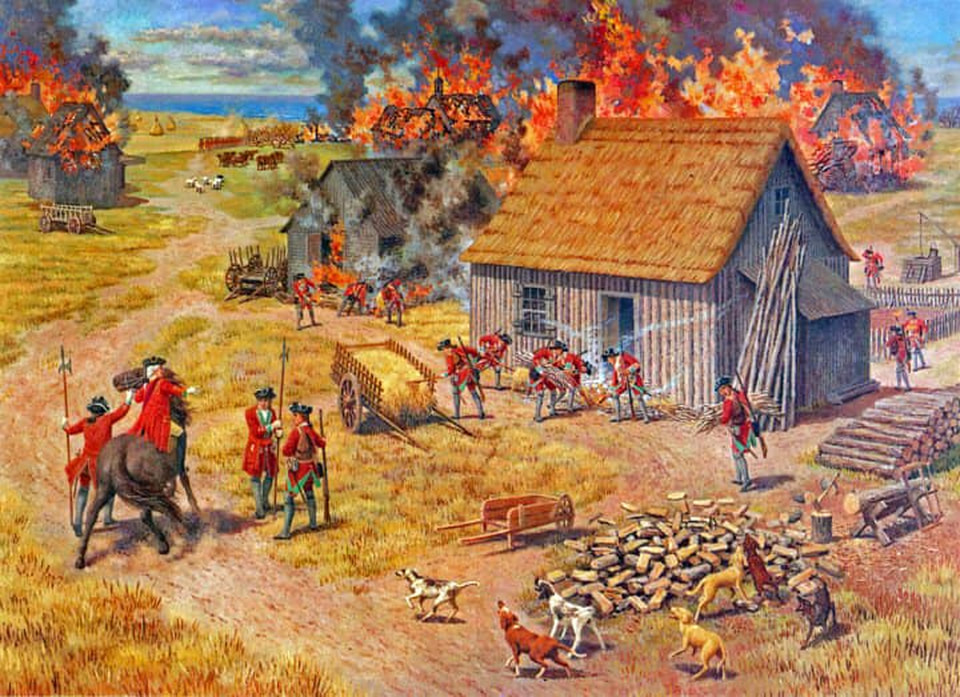

The Minas Basin area was not spared the negative effects of the conflicts. In both 1696 and 1704, expeditions from New England, led by Benjamin Church, came to different parts of Acadie. In the latter expedition, the attackers devastated the community at Grand Pré. They burned houses, carried off prisoners, and broke the dykes to let in sea water, because they knew that the enclosed dykeland was crucial to the Acadians’ agricultural output. A contemporary account says that the soldiers dug “down the dams [dykes], and let the tide in, to destroy all their corn, and everything that was good.” Once the force left, the Acadians returned to the area, rebuilt their houses and repaired their dykes to begin anew.

|

When the war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, one of the terms of the peace agreement was to have a major impact on the Acadians and their settlements. The clause in question saw France transfer sovereignty over Acadie/Nova Scotia to Great Britain. The British presence in Nova Scotia was small at the time, with few British settlers and small garrisons only at Annapolis Royal and Canso. Most of the territory either remained under the control of the Mi’kmaq or was home to growing Acadian villages.

Nonetheless, beginning in 1713 and increasingly in the years that followed, British officials regarded Acadians as a people owing obedience to their monarch, with all the obligations that this entailed. The question of the Acadians’ loyalty was one that would not be settled – to the satisfaction of the British officials – between 1713 and 1755. In fact, this question played a major role in the sequence of events that led to the forcible removal of Acadians from Grand Pré beginning in 1755.

|

|

Settling in Grand Pré |

|

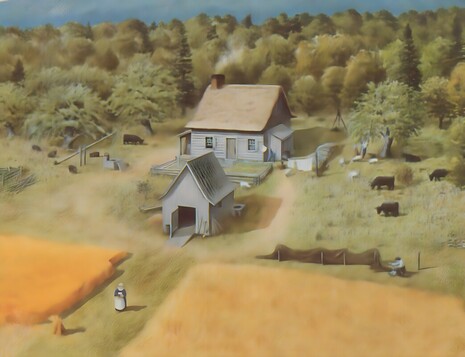

When the French settlers came to Les Mines (Grand Pré) from Port Royal in the 1680s, they occupied lands that were initially part of the seigneurie of Alexandre LeBorgne de Bélisle who was the seigneur of Port Royal. As was the custom in New France, the settlers were granted lands shaped as long strips that extended away from the nearest water course.

|

This seigneurial pattern, common to New France and somewhat to Acadie, allowed each settler to have access to the water, to varying degrees of land quality, and to woodlots. It was the task of the settler to clear the land for farming. The seigneur would collect rent and build a mill for the community.

For Grand Pré, little is known about the strength of the relationship between the seigneur and his settlers, or about the first years of settlement. LeBorgne de Bélisle had tried to reinstate the authority of the seigneur after years of nominal British authority (1654–1670), but he seems to have failed. Even so, it is most likely that the settlers adopted the typical seigneurial land pattern, although no maps or description have survived to confirm that. Historians and archaeologists believe that the settlers of Les Mines did in effect implement a seigneurie, and that tangible and visible evidence of that landscape form exists today.

|

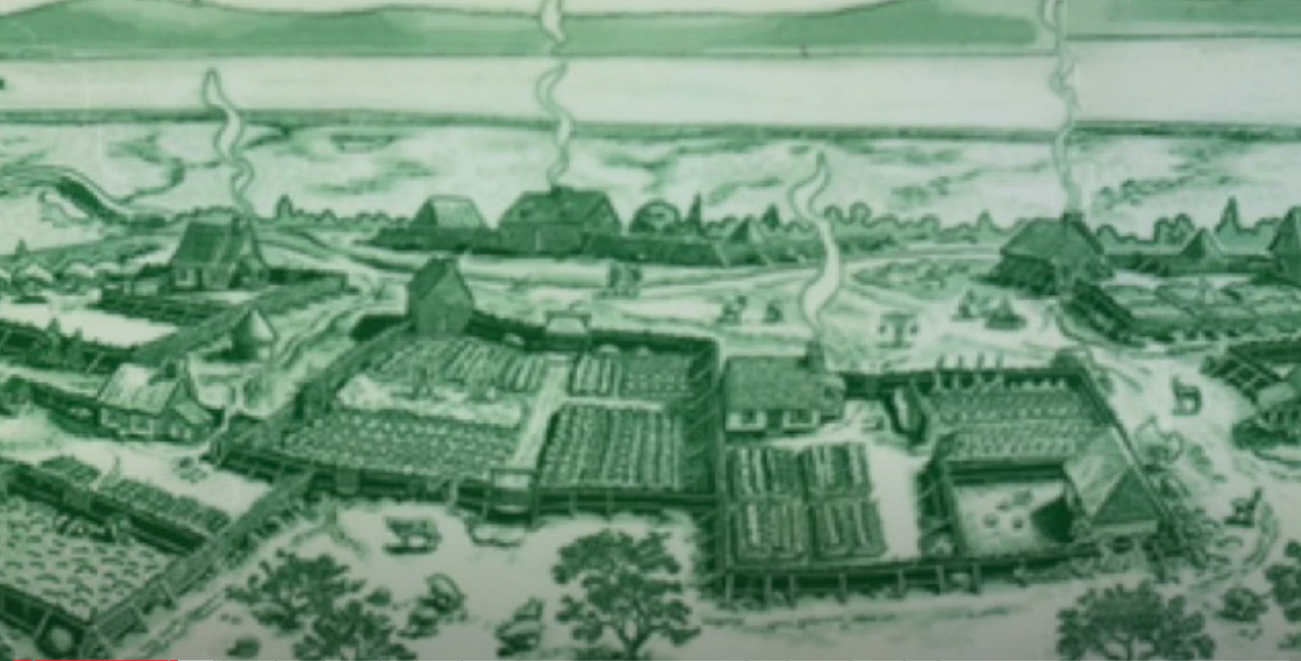

While the first settlers may have adopted the seigneurie, their settlement pattern evolved in response to the creation of the dykeland. They created farmland by transforming marshland rather than by clearing woodland. In order for the community to be close to their work area without settling on the newly created land, they built their homes alongside the marsh. The Acadians erected their houses, barns, mills, and other buildings on the adjacent upland and created a system of roads and footpaths to link them with other Acadian villages.

Over time, they cleared land from the uplands to make way for the buildings, roads, and paths, as well as to create some farmland and allow access to the woodlots. From these lots they extracted the building material for their houses, barns, aboiteaux, and dykes. From the 1680s onwards, three generations of Acadians gradually enclosed and converted the marsh (la grand pré).

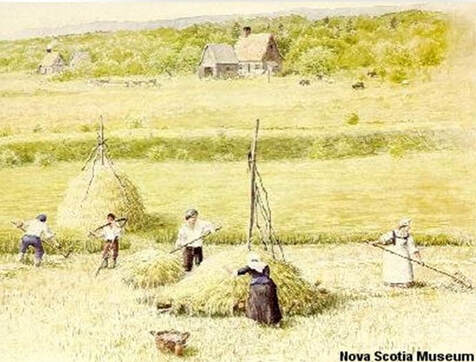

In 1670, the new French governor of Acadie observed the settlements close to Port Royal and wrote, “On these dykes they raise with so little labour large crops of hay, grain and flax, and feed such large herds of fine cattle that an easy means of subsistence is afforded, causing them altogether to neglect the rich upland.” This comment, which ignores the backbreaking work that went into creating the dykelands, could well have applied to Grand Pré a decade later. In Grand Pré, the great fertility of the dyked marsh was an important key to the region’s success.

By the 1680s, Acadians already had half a century’s experience of transforming land in Acadie. The first recorded evidence of dykelands comes from the Port Royal area at the site of the first successful permanent French settlement in North America. While the origin of land transformation in Acadie is not recorded, there are two possible sources of the Acadians’ knowledge: one individual and one collective. It seems that these sources may have been at work simultaneously.

By the 1680s, Acadians already had half a century’s experience of transforming land in Acadie. The first recorded evidence of dykelands comes from the Port Royal area at the site of the first successful permanent French settlement in North America. While the origin of land transformation in Acadie is not recorded, there are two possible sources of the Acadians’ knowledge: one individual and one collective. It seems that these sources may have been at work simultaneously.

|

In 1636, Isaac de Razilly, governor of Acadie, enlisted five sauniers from western France for the purpose of “dyking the marsh” (faire des marais) at Port Royal, which may be interpreted as either creating saltpans or dyking for agricultural purposes. Their presence in the colony is confirmed in the roll call of their ship the Saint Jehan, a list where they were specifically identified along with dozens of other settlers from different parts of France, but mainly from the coastal region of Aunis and Saintonge. These sauniers were keepers of the centuries-old expertise of building dykes and draining lands in western France. Dykelands were indeed created in Port Royal as confirmed by the 1670 observation by the French governor at the time. Historians, however, have lost track of these sauniers, and their impact is difficult to assess. |

While there is no indication that salt collection per se was ever attempted in Acadie, it is reasonable to believe that these sauniers would have had a role in carrying knowledge acquired in Europe and adapting it to the environmental conditions of Acadie.

The other possible origin, one noted at the turn of the 20th century by historian William Francis Ganong and more recently by historians Yves Cormier, John Johnston, and Ronnie-Gilles LeBlanc, is a collective knowledge of dyke building that the French settlers likely brought with them to the new world. The majority of these settlers came from western France, where marshy areas had been transformed and reclaimed over centuries to create much-needed land. In particular, they came from Poitou, Aunis, and Saintonge areas along the Atlantic coast with large expanses of marsh. These areas were the home of peoples that had mastered the skills of dyking, land drain-age, and salt extraction since the Roman period. These regions were also the target of intensive land transformation as early as the 11th century under the direction of religious and political authorities. By the late 16th century, salt water had again flooded many of those large tracts of transformed lands, largely as a result of the dyking and drainage works having sustained great damage from the religious wars that swept across Europe in that century.

However, the knowledge of dyking and drainage was not lost. Many dyking systems still remained, particularly in Poitou, Aunis, and Saintonge, and local populations made constant efforts to maintain them for agricultural use and to protect their settlements. Some of the settlers who came to Acadie at the beginning of the 17th century certainly carried this knowledge with them. Its application in Acadie is an extension of that tradition from Europe to North America and reflects a simple dyking and drainage experience that predates the large engineering works of the 17th century. The use of more advanced technology to drain the dykes was never necessary. The extreme tides at Grand Pré make mechanized draining unnecessary, because the low tide is well below the level of the dykelands (see Figure 2–25).

However, the knowledge of dyking and drainage was not lost. Many dyking systems still remained, particularly in Poitou, Aunis, and Saintonge, and local populations made constant efforts to maintain them for agricultural use and to protect their settlements. Some of the settlers who came to Acadie at the beginning of the 17th century certainly carried this knowledge with them. Its application in Acadie is an extension of that tradition from Europe to North America and reflects a simple dyking and drainage experience that predates the large engineering works of the 17th century. The use of more advanced technology to drain the dykes was never necessary. The extreme tides at Grand Pré make mechanized draining unnecessary, because the low tide is well below the level of the dykelands (see Figure 2–25).

(Figure 2-25) Illustration of a cross-section of the dykelands at Grand Pré, including the tidal range, salt marsh, aboiteau system and fields. Note the aboiteau refers to the section of the dyke surrounding the sluice; this cannot be accurately represented in a cross-section, but can be seen in Figure 2–26. Additionally, the tidal zone at Grand Pré includes mudflats that extend for hundreds of metres. In order to illustrate the mean tidal range, this diagram considerably reduces the mudflats.

At the turn of the 17th century, western France was again the focus of large projects, this time under the engineering leadership and the financial backing of the Dutch. Invited by the royal and seigneurial authorities, the Dutch undertook significant work in France to reclaim those lands through a more systematic and improved system of drainage that involved canals, channels, gates, and landscape design. The Dutch made a significant contribution to land reclamation in those regions, primarily by introducing these engineering designs works. They had a lasting impact on the design and technology of dyking and drainage.

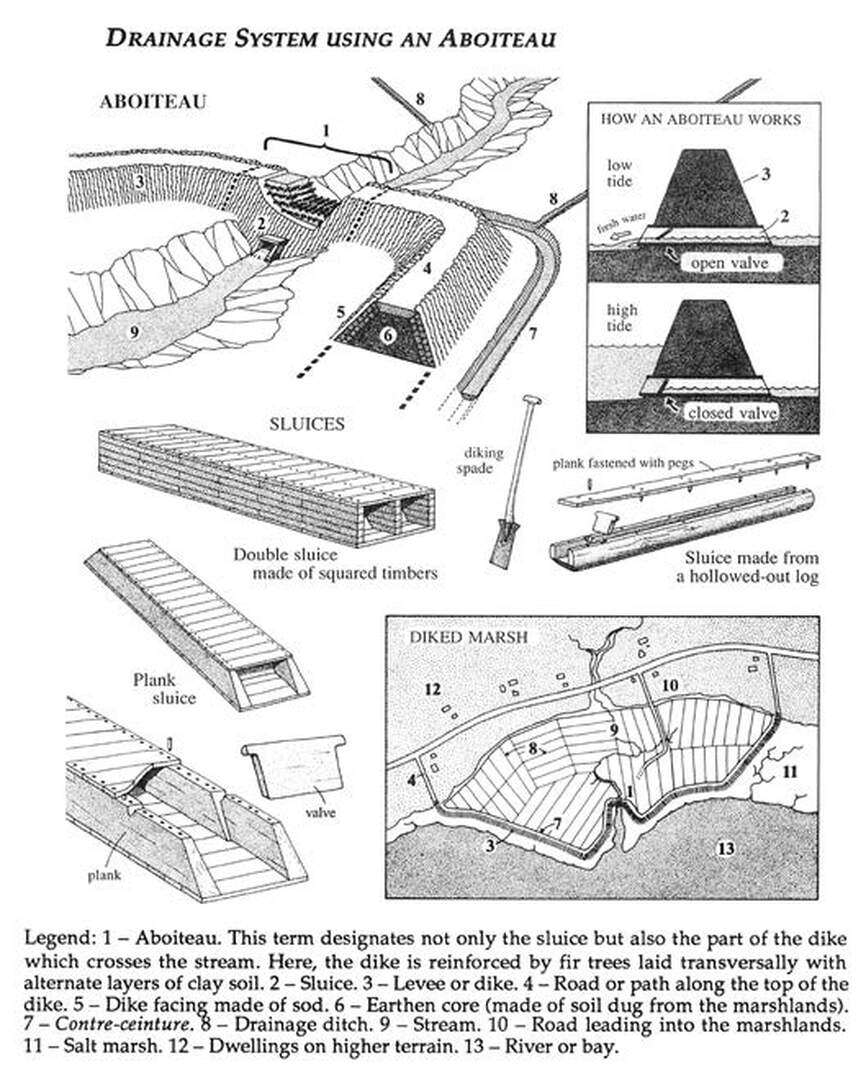

The technology that the Acadians used to transform wetlands and marshes could not have been simpler: special spades, pitchforks, axes, and hollowed-out tree trunks. Much more important than the tools was the ingenuity of the people to read the natural drainage systems of the marshes and then to build dykes that channelled the flow of those creeks in only one direction, discharging into the sea. One element of the Acadians’ success was to use sod cut from the original wetlands in their earthen dykes. In a process similar to peat extraction in western Europe, special spades were used to cut bricks of sod in specific sizes and shapes that were then assembled to form the dyke. The grasses and rushes in the sod could withstand being covered by salt water for many hours each day. They also had deep and densely matted root systems that anchored them when the sea water swirled over them, protecting the exposed sides of the dykes at high tide. Cutting the sod and assembling the dykes were a communal undertaking because of the skills, efficiency and speed the work required.

The technology that the Acadians used to transform wetlands and marshes could not have been simpler: special spades, pitchforks, axes, and hollowed-out tree trunks. Much more important than the tools was the ingenuity of the people to read the natural drainage systems of the marshes and then to build dykes that channelled the flow of those creeks in only one direction, discharging into the sea. One element of the Acadians’ success was to use sod cut from the original wetlands in their earthen dykes. In a process similar to peat extraction in western Europe, special spades were used to cut bricks of sod in specific sizes and shapes that were then assembled to form the dyke. The grasses and rushes in the sod could withstand being covered by salt water for many hours each day. They also had deep and densely matted root systems that anchored them when the sea water swirled over them, protecting the exposed sides of the dykes at high tide. Cutting the sod and assembling the dykes were a communal undertaking because of the skills, efficiency and speed the work required.

Along with using the strong, dense plant growth in the sod, the Acadians took advantage of the natural drainage patterns of the marsh by building aboiteaux in the small creek beds that drained the marshes at low tide. The aboiteau, a term used in Acadie, refers to the section of the dyke surrounding the sluice, as well as to the completed dyking project. The sluices each had a clapet (clapper), a wooden valve that allowed fresh water out of the sluice and into the river or bay at low tide but did not allow sea water back in during high tide (see Figure 2–26).

(Figure 2-26) An aboiteau opens to allow fresh water to drain from the marsh and, under the effect of the rising tide, closes to prevent sea water from entering. |

Once a section of marsh was enclosed, the fresh water from rain and snow melting gradually washed the salt out of the top layers of the soil. The desalination process generally took two to three years for each plot of dyked land. The aboiteau approach used by the Acadians was imaginative and ingenious, an adaptation of techniques used in Europe and elsewhere for centuries before French colonists arrived in North America.

|

Impressed by the fertility and productivity of the initial transformed lands in Acadie, the Acadians would go on, until 1755, transforming many marshes of different sizes along tidal rivers and various coves and bays around the Bay of Fundy, in many parts of today’s Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Acadians came to be known as défricheurs d’eau (water pioneers), to distinguish them from other colonists in North America who created farmland by clearing the forest. The Acadians did clear some upland areas for their villages, orchards, gardens, and livestock, but the dominant element in their agriculture, highly unusual in North America, was to claim the tidal marshes by enclosures. Though the Acadians used marsh enclosures to give themselves agricultural land in many different areas, the high tidal range at Grand Pré presented exceptional challenges. Along the Annapolis Basin, where the first Acadian dykes were erected, the tidal range varies from 4 metres to a maximum of 8.5 metres. Within the Minas Basin at Grand Pré, the mean tidal range is 11.61 metres, and the highest tides in the basin reach more than 16 metres. To the Acadian dyke builders, countering this churning volume of sea water required toughness and ingenuity. They had to devise a building technique that would not wash away as the dyke was being built, dexterity to assemble the different parts of the dyke effectively, collective coordination to transform large tracts of lands quickly, and great labour to build large dykes that could withstand the pressure of such formidable amounts of water (see Figure 2–27).

|

(Figure 2-27) View of a 19th century aboiteau, illustrating the elaborate structure required to withstand the pressure of the tides

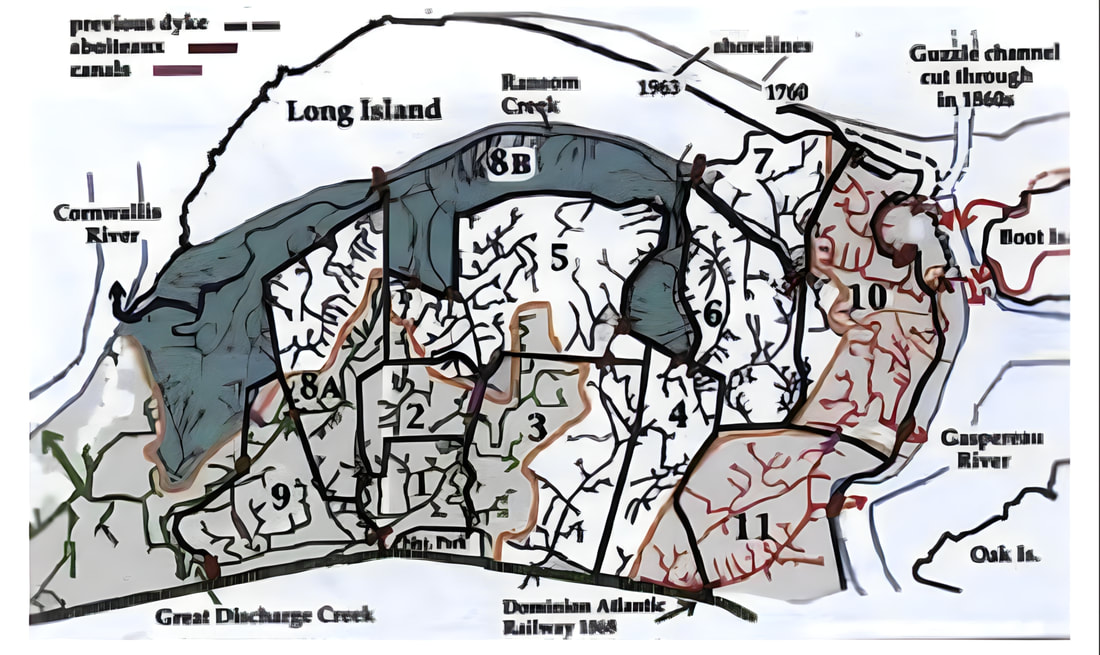

Yet dyking the marshlands was also a major agricultural opportunity. Between 1680 and 1755, the Acadians took on the project of excluding the sea and claiming the highly fertile tidal marshes. They appear to have begun with the easiest part of the marsh, in the centre not far from the upland shore. Once they had successfully enclosed that area, they moved on to a series of other dyking projects. Biologist and dykeland historian Sherman Bleakney offers a likely construction sequence of the dykeland enclosures in his book Sods, Soils and Spades (2004) (see Figure 2–28).

|

(Figure 2-28) Biologist and historian Sherman Bleakney's map of the Grand Pré dykelands

|

Construction began near the centre and progressed in large sections around that first enclosure in 12 sequences that follow the three main creeks and their drainage watershed. Gradually, the Acadian farm families of Grand Pré turned nearly all of la grand pré into agricultural land.

As the Acadians transformed la grand pré, the adjacent village grew steadily. Within a few decades, the Grand Pré area had become the most populous of all the Acadian settlements. Acadians began to export their surplus production, especially grain, to both French and British settlements. The exports were shipped in vessels that anchored in the Minas Basin and loaded and unloaded their cargoes at the landing point (now known as Horton Landing) on the Gaspereau River. Eighteenth-century British and French commentators acknowledged the unrivalled fertility of the dykelands created by the Acadians. For example, Grand Pré was renowned for its grain production. |

It is noteworthy that the dyking projects at Grand Pré, and in most other Acadian settlements in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, were community projects (see Figure 2–29). Archival evidence and first-hand accounts from travellers and authorities, in the 18th and 19th centuries, indicate that communities had rules to guide collective work for the benefit of all. The main rule governing collective management was that each landowner contributed to the building and maintenance of dykes and aboiteaux by providing either labour or financial compensation.Once a section of marsh was enclosed, the fresh water from rain and snow melting gradually washed the salt out of the top layers of the soil. The desalination process generally took two to three years for each plot of dyked land. The aboiteau approach used by the Acadians was imaginative and ingenious, an adaptation of techniques used in Europe and elsewhere for centuries before French colonists arrived in North America.

|

It is clear also that collaboration did not mean collective ownership. Evidence suggests once the collective transformation had been completed, the land was allotted through a lottery system. In order to consolidate fields or acquire better land, landowners would then trade or buy fields. An entrepreneurial spirit characterized the farming activities of the settlers. Local farm families made the decision to transform the vast wetlands of Grand Pré, and their children and grandchildren continued the work. Most other Acadian land transformations followed the same process. |

The only exceptions were the original dykes initiated at Port Royal in the 1630s and the uncompleted project in the Tantramar marshes of the Chignecto area that straddled the border between New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in the 1750s. These two projects were initiated and controlled by a leader or hierarchical figure. By contrast, the more common community approach helped to shape the Acadian identity and strengthen the ties of their close-knit society over the long term.

|

|

Continuing French and

|

|

As France and Great Britain continued to jockey for imperial domination of North America throughout the 18th century, most Acadians, including those at Grand Pré, wanted to stay out of the conflict and be accepted as neutrals. Unfortunately, neither French nor British officials were willing to accept that position. Both powers wanted the Acadians, or the “French neutrals” as the British and Anglo - Americans labelled them, to support their cause and, ideally, to fight for it.

|

Signing the Oath of Allegiance to the King of Great Britain

|

The French saw the Acadians as natural allies, since they were Roman Catholics, mostly of French descent, and spoke French. The British, on the other hand, viewed the Acadians as subjects of their king since the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. A few Acadians were pro-French and a few others worked with the British, but most were caught in the middle between competing imperial aspirations. Following the Treaty of Utrecht, the Acadians were expected to take an oath of allegiance to the King of Great Britain. This they at first refused to do, in an attempt to maintain their identity and their neutrality.

|

In addition to their concern over the Acadians, the British were also troubled with their relations with the Mi’kmaq. As the British strengthened their position in New England and Acadie at the beginning of the 18th century, they signed treaties with the Aboriginal peoples of those regions, including a treaty signed in Boston in 1725 with the Wabanaki Confederacy intended to ensure the protection of existing British settlements from attack. The Mi’kmaq, who were part of the Confederacy, agreed to the treaty in 1726 after several modifications.

In 1729–30, Acadians throughout mainland Nova Scotia agreed to a modified oath of allegiance proposed by the British governor based at Annapolis Royal. The governor assured the Acadians that they would not be forced to take up arms against the French and the Mi’kmaq, and that they would be allowed to remain neutral. Events in the 1740s and 1750s, however, led later British administrations to revisit the question of Acadian neutrality.

After three decades of peace, Great Britain and France again found themselves in conflict during the War of the Austrian Succession (1744–1748). The main theatre was in Europe, yet Canada saw its share of action. Several incidents at or near Grand Pré had a long-term impact on the Acadian population.

|

In the summer of 1744, a military expedition from the French stronghold at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island advanced through the main Acadian communities, including Grand Pré, appealing to the Acadian men to join the campaign. Few answered the call. Acadians wanted to remain neutral, and they had a harvest to bring in. While the overall Acadian response in 1744 disappointed the French, it worried the British, who had hoped to see them actively turn against the French.

|

The following year, 1745, the French launched an unsuccessful attack on the British base at Annapolis Royal. At around the same time, a large army of provincial soldiers from New England, supported by British warships, captured Louisbourg. In 1746, France outfitted a massive expedition to cross the Atlantic on a mission to regain Louisbourg, to take Annapolis Royal, and to compel the Acadians to commit themselves to the French cause. The expedition ended in disaster because of delays, storms and illnesses.

|

|

The Attack at Grand Pré

|

|

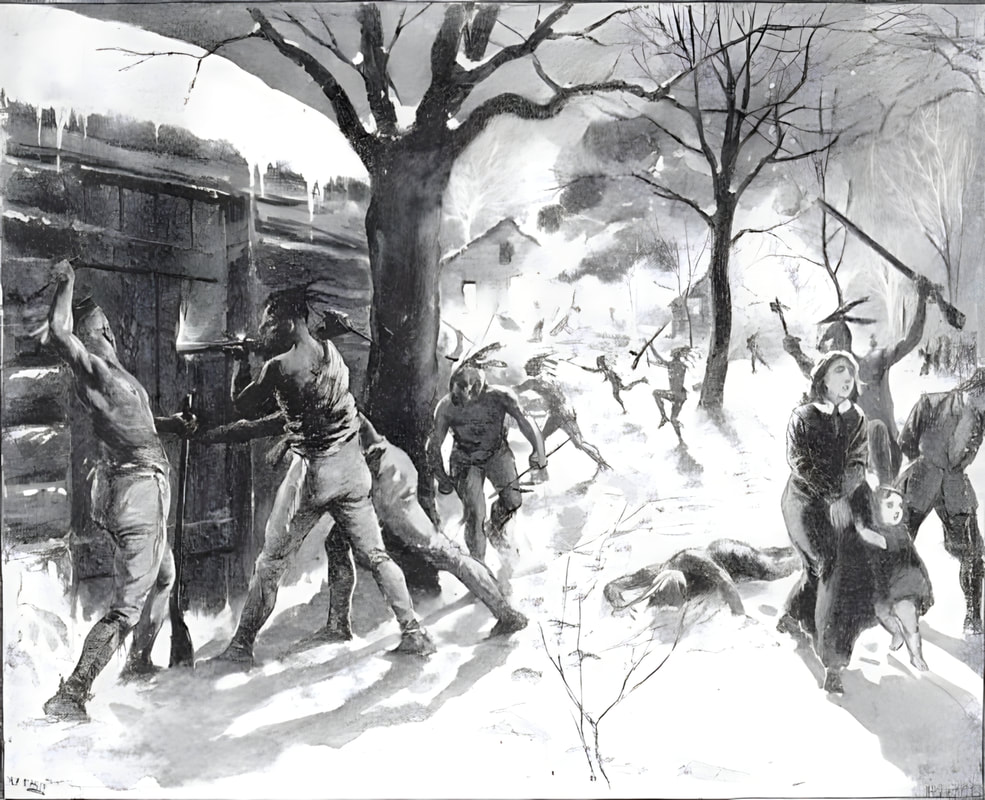

In the early morning hours of 11 February 1747, in the middle of a blinding snowstorm, the French, Maliseet, and Mi’kmaq force caught the New Englanders by surprise. Known to history as the Attack at Grand-Pré, the encounter left as many as 80 New England men dead, including their commander. The bodies of the soldiers were interred in a mass grave, while their commander was buried separately nearby.

|

(Figure 2–30) Attack at Grand-Pré.

The New Englanders ignored the warnings, thinking the severe winter conditions made an attack unlikely.

Grand-Pré was the scene of a surprise attack on Col. Arthur Noble’s detachment of British troops from Massachusetts who were billeted in the houses of the inhabitants. A French and Indian force under Coulon de Villiers broke into the British quarters at 3 A.M. during the snowstorm with close fighting, Noble and about 80 of his men were killed. On the 12th the British capitulated on the condition that they be allowed to return to Annapolis Royal. The French departed soon after; and the British resumed their uneasy possession of mainland Nova Scotia. The incident was to loom large in the thinking of some British leaders in 1755, when they decided to implement a massive removal of the Acadians.

|

Both the French and the British strengthened their positions in the Atlantic region in the late 1740s. In the autumn of 1746, in response to earlier French actions in the area, the British sent roughly 500 New England soldiers to establish a post in the village of Grand Pré. The Anglo-American troops took over several houses on the uplands overlooking the reclaimed marsh and settled in for the winter. A few hundred kilometres away in the Chignecto region near the New Brunswick border, a contingent of 250 French soldiers and 50 Maliseet and Mi’kmaq warriors heard reports of the New Englanders’ occupation of Grand Pré. Despite being outnumbered two to one and facing the hardships of mid-winter travel, they set out for Grand Pré in January 1747. They were joined or assisted by a small number of Acadians who were sympathetic to the French cause. At the same time, some pro-British Acadians warned the New England soldiers that an attack might be imminent. The New Englanders ignored the warnings, thinking the severe winter conditions made an attack unlikely.

|

|

|

Planning New Settlements |

|

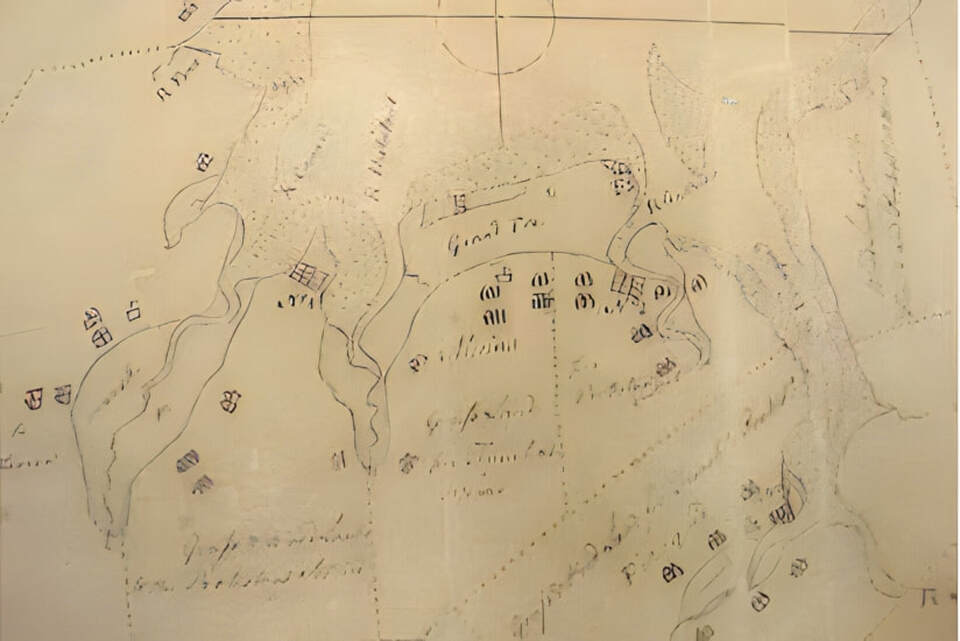

This 1748 map shows plans to settle Protestants at Grand Pré, labelled as “No 2” in this map, prior to the Acadian Deportation. The British authorities had planned settlements (shown as grids on this map) in the immediate vicinity of the existing Acadian settlements (illustrated as concentrations of houses here). Note, the large concentration of houses and the church (shown as a square with a cross) at Grand Pré, in the middle of the map, illustrating the importance of the settlement of Grand Pré.

When the War of the Austrian Succession ended in late 1748, the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle returned Louisbourg to the French. Not long after, both France and Britain expanded their military presence in Atlantic Canada. France’s major move was to send an expedition of several thousand colonists to re-occupy Louisbourg in 1749. From 1749 to 1751, the French also established a post at the mouth of the Saint John River and two forts in the Chignecto region, at Beauséjour and Gaspareaux. The British, meanwhile, sent a massive expedition to establish Halifax in 1749 as a counterbalance to Louisbourg. Over the next few years, the British also established several new posts, forts, and settlements beyond Halifax. They included Fort Edward within the Acadian community at Pisiquid, a small fort at Vieux Logis (Horton Landing) near Grand Pré, Fort Lawrence in the Chignecto region (opposite Fort Beauséjour), and a sizeable new town of “foreign Protestants,” mostly of German and Swiss origin, at Lunenburg, on Nova Scotia’s southeastern shore.