Individuals such as John Frederic Herbin and Father André-D. Cormier, private companies such as the Dominion Atlantic Railway and the Société nationale l’Assomption, and the Acadian community transformed Grand Pré into a historic site and a major tourist attraction in North America. The commemorative monuments, buildings and garden they created were a symbolic reclaiming of the Grand Pré area by the descendants of the people who were forcibly removed in 1755. As a result, for people of Acadian descent, Grand Pré became the most cherished of all their historical sites.

|

|

A Century of

|

|

In 1907, John Frederic Herbin, a jeweller and poet – of Acadian descent – in nearby Wolfville, purchased the land at Grand Pré that contained the most prominent ruins that were said to date back to before 1755. Herbin had published a book of local history in 1898 that had echoed the opinions of historian Henri L. d’Entremont, who had argued for the need to honour Acadian ancestors at Grand Pré.

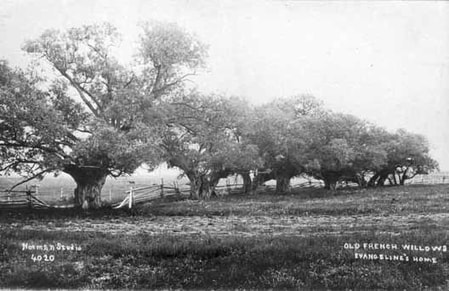

The oral tradition of the time held that the ruins on Herbin’s new property were vestiges of the old Acadian parish church, Saint-Charles-des- Mines, the same church in which Acadian males were imprisoned on 5 September 1755. Not far from those ruins was a well, also said to date back to the Acadian period (see Figure 2–40). A little farther on was the old Acadian burial ground or cemetery. Nearby were a number of old willow trees, which in the oral tradition were said to have been silent witnesses to the events of 1755 (see Figure 2–41).

The purchase was a public acknowledgement that this land was significant to the Acadians. Herbin’s vision that “...The Grand Pré memorial field is the outstanding historical landmark most closely associated with the occupation of the Acadians of this country for seventy years” convinced others to protect and commemorate the site.

In 1908, the Government of Nova Scotia passed an Act to recognize and incorporate the trustees of the “Grand-Pré Historic Grounds.” This was the first attempt by any government at any level to safeguard the site at Grand Pré.

In 1917, Herbin and the other trustees sold the property with the ruins on it to the Dominion Atlantic Railway (DAR) on the condition that the church site be deeded to the Acadian people so they could erect a memorial to their ancestors. The following statement by Herbin explains his vision:

In 1908, the Government of Nova Scotia passed an Act to recognize and incorporate the trustees of the “Grand-Pré Historic Grounds.” This was the first attempt by any government at any level to safeguard the site at Grand Pré.

In 1917, Herbin and the other trustees sold the property with the ruins on it to the Dominion Atlantic Railway (DAR) on the condition that the church site be deeded to the Acadian people so they could erect a memorial to their ancestors. The following statement by Herbin explains his vision:

The proposed restoration of the Memorial Park will consist of buildings to be erected by the Acadians upon the site of the St. Charles’ Church. A statue of Evangeline on a stone base with bronze tablets will be erected on the space between the stone cross and the old well. Roads, walks, flower beds and structures to mark the various spots, will add to the attractiveness of the place. From there the great stretch of the Grand Pre lies as a monument of unremitting labour.

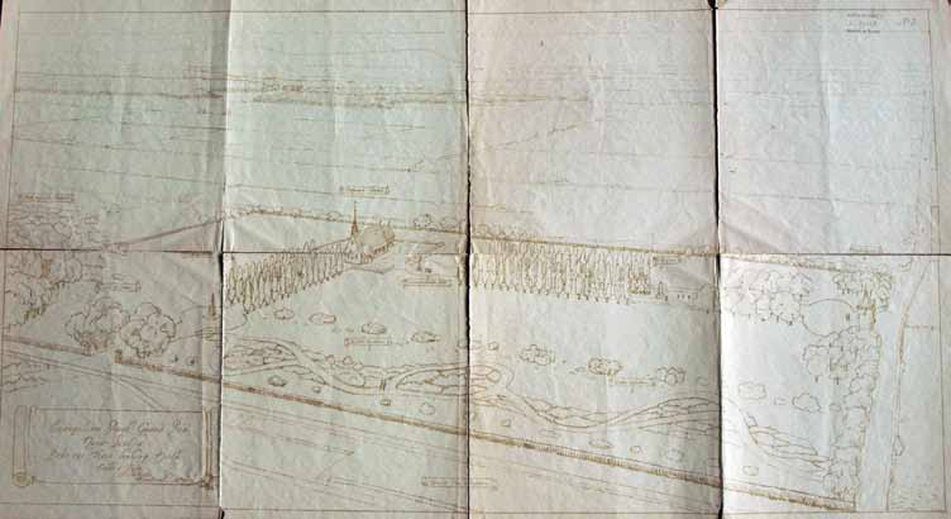

The DAR assumed responsibility for the Grand Pré site and engaged renowned Canadian architect Percy Nobbs to bring Herbin’s vision to fruition. The architect developed a detailed landscape plan for the grounds, complete with pathways, flower beds and potential monument locations

(see Figure 2–42).

(see Figure 2–42).

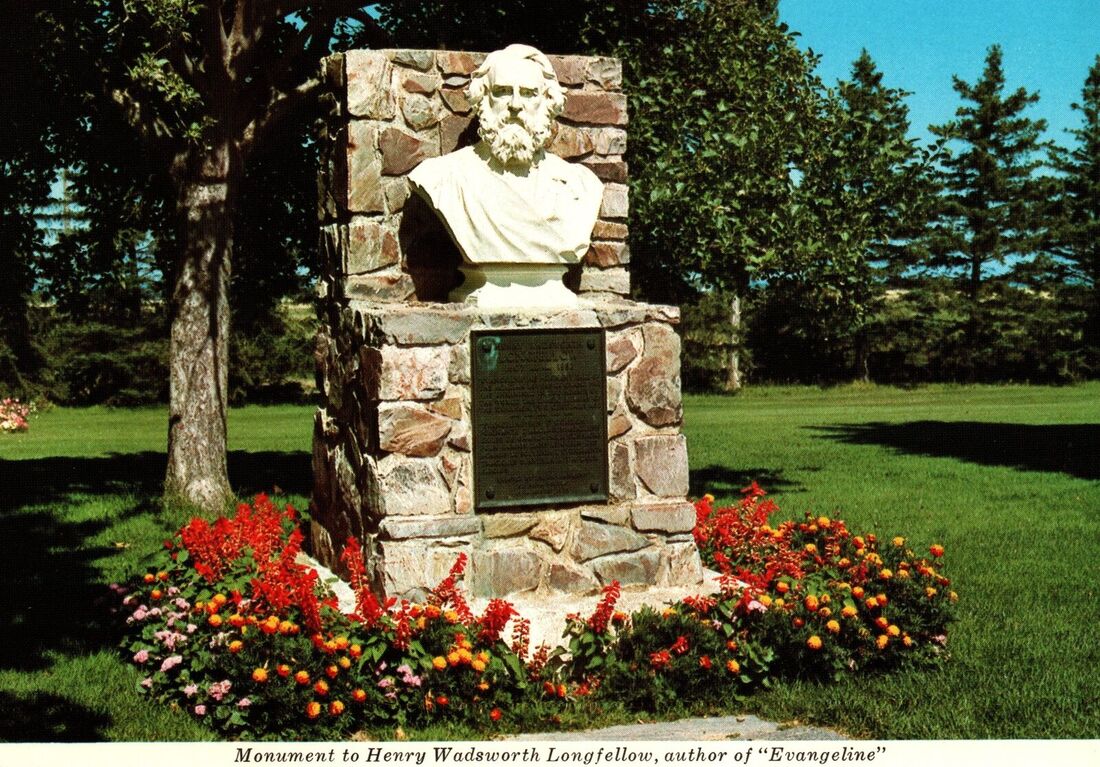

With Nobbs’s drawings in hand, the rail company developed a “park” for tourists who wanted to see the spot Longfellow had made famous in his epic poem. The park-like setting – a cross between a jardin des plantes and a commemorative cemetery – encouraged many visitors to reflect on the tragedy of the Acadians in 1755. The first major artistic element added to the landscape was a bronze statue of Evangeline, unveiled in 1920. The statue was the work of renowned Québec sculptor Henri Hébert and was inspired by a design by his father, sculptor Louis-Philippe Hébert (see Figure 2–43). The Hébert artists were of Acadian descent.

|

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s the DAR, the provincial department responsible for tourism, and many private companies used images and slogans employing the Evangeline theme and Grand Pré association to sell their products. At the same time, there was a marked commercialization of Evangeline: various depictions of the fictitious heroine showed up on a range of products from soft drinks to car dealerships to chocolates.

Despite the commercial overlay and the frequent tie-ins with a literary figure, Acadians during the 1920s were becoming increasingly interested in Grand Pré and attached to it as an evocative site that was a symbolically reclaimed homeland and a legacy of the tragedy of their forced removal. In 1919, Father André-D. Cormier, a priest from New Brunswick, took part in the negotiations to acquire the property in Grand Pré to build a church. In 1921, the Société nationale l’Assomption (predecessor of today’s Société nationale de l’Acadie [SNA]) held part of its eighth national convention at Grand-Pré. At that convention, the SNA took official possession of the church site and launched a fundraising campaign to build a Memorial Church (église-souvenir) on or near the site of the presumed ruins of the parish church (see Figure 2–44). Father Cormier became the founding president of the Memorial Church Committee and began organizing several fundraising campaigns. The Acadian diaspora from the maritime provinces, Québec, Louisiana, and France was solicited for donations. The construction of the church reflected the growing wave of Acadian nationalism that had been on the rise since the 1880s. Having achieved a number of successes in asserting Acadian rights and identity, the Acadian community now felt the time was right for such a symbolic gesture. The Acadian community’s commemoration efforts at Grand Pré continued in 1923, when they raised funds for a sculpture of the Acadian patron saint, Notre-Dame de l’Assomption, to be placed inside the newly completed church (see Figure 2–45 and 2–46). The next year, a group of Acadians from the maritime provinces and Québec, as well as non-Acadians interested in Acadian history, erected a poignant symbol of the 1755 Deportation. That new marker was an iron cross, referred to as the Deportation Cross, which was erected beside the DAR rail line, about two kilometres from the Grand Pré site. It was placed by a dry creek bed that was believed at the time to be where their ancestors had embarked in small boats during the Deportation. Later research found that the actual embarkation spot was at Horton Landing. The cross was relocated there in 2005. Up to the mid-1950s, concerned citizens and organized groups, primarily within Canada but also from the United States, were responsible for all the commemorative action and development at Grand-Pré. By 1955, all the major elements of what has now become a lieu de mémoire (discussed later in this chapter) had been in place for three decades: the Memorial Church, the Statue of Evangeline, the Deportation Cross, the old willows, a stone cross to mark the Acadian burial ground, the well, and the flower beds. In May 1955, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, the arms-length advisory body that recommends designations of national significance to the responsible federal minister, concluded that the “Grand Pré Memorial Park possesses historical features which would make it eminently suitable as a National Historic Park.” Negotiations took place over the next year. On 14 December 1956, the Société nationale l’Assomption finalized the sale of Grand Pré to the Government of Canada. Five years later, in 1961, the federal department responsible for historic sites officially opened Grand-Pré National Historic Site of Canada. Since that transition, Parks Canada has maintained the original commemorative monuments and worked closely and collaboratively with representatives of the Acadian community. Since the mid-1990s, the Société Promotion Grand-Pré, a new group representing the Acadian community at Grand-Pré National Historic Site of Canada, has worked closely with Parks Canada to promote and enhance the national historic site, supporting the tradition of erecting memorials and organizing events that reflect the Acadian identity and attachment to the site. |

|

|

A Place that Brings Together a Diaspora |

|

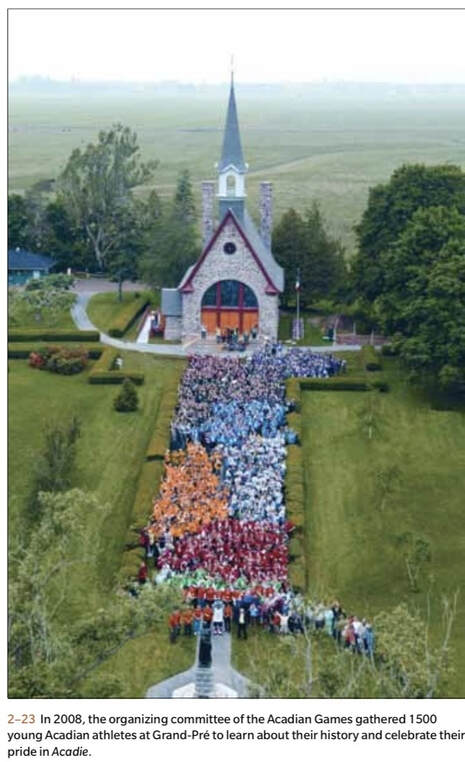

Since the beginning of the 20th century, many events have taken place in Grand Pré that have secured its role as the heart of Acadie and the place most closely associated with Acadian identity. These include Acadian congresses, events commemorating the Deportation, pilgrimages, and cultural events.

|

|

Dyke and Aboiteau Maintenance at Grand Pré |

|

|

This strong symbolic landscape has remained a strong agricultural landscape. The dykes at Grand Pré are maintained, and new expansions have been partially built as well on the west side. The northeastern dyke on Long Island and parts of the eastern dykes were built in the 1940s, some behind the previous lines of dykes, others in front. The Wickwire Dyke, rebuilt in the 19th century, was again abandoned in 1932 following years of degradation from violent storms. It was rebuilt for a second time in 1959. The footprints of sections of other dykes were moved to maintain their ability to withstand the tides. In each case, the decision to build dykes was based on the capacity to maintain the integrity of the system of dykes and aboiteaux.

The dykes built in the 1940s, along with the rebuilding of the Wickwire Dyke, were part of a government initiative known as the Emergency Programme. In 1943, the federal government and the provincial governments of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick established the Maritime Dykeland Rehabilitation Committee (see Figure 2–52). An even more ambitious initiative followed in 1948, with the creation of the Maritime Dykeland Rehabilitation Administration through an act of the Parliament of Canada. The task of maintaining the condition of all dykelands in the maritime provinces was thus treated as a single project that unlocked major financial resources. By the late 1960s, all major projects of rebuilding dykes and replacing aboiteaux had been completed. Supervision of the dyke maintenance was transferred to the provinces, where the responsibility remains to this day. |

Throughout three centuries of evolution and changes, Grand Pré farmers have retained their distinctive approach to building and maintaining the original dykeland. The design of aboiteaux has not changed, although new materials now enhance their reliability and lifespan. The dykes are still built from earth, and the native vegetation continues to protect them. For 300 years, local farmers have experimented with different combinations of materials to strengthen the dykes – sometimes using rocks, sometimes wooden planks held with rods as facing (known as a “deadman”) – yet the basic technology is the same. The creeks have been kept intact to ensure the proper drainage patterns.

Today’s farmers, some of New England Planter descent and many of Dutch origin who arrived after the Second World War, continue to retain the knowledge of dyke building and maintenance. While few local farmers still know how to handle a spade to cut sod into bricks, many understand the appropriate design and the inner workings of drainage and of aboiteaux, as evidenced by the private dykes and aboiteaux that continue to be built. The Department of Agriculture has some of this knowledge, but it needs the experience of the farmers to maintain the dykes.

Community-based management continues today in the 21st century. The farmers of the Grand Pré Marsh Body own the land individually but share resources and make decisions collectively about maintaining the marsh. The farmers do not have direct responsibility for the dykes but retain an essential role in their maintenance and the experience of building them. Their management approach keeps alive the spirit of collective concern for this agricultural landscape and the individual desire to thrive. Throughout the major federal and provincial government projects of the past 70 years, the Grand Pré Marsh Body maintained its role. The Grand Pré Marsh Body’s recorded minutes and archives go back to the late 18th century. It is the oldest and most active organization of its type in North America.

Today’s farmers, some of New England Planter descent and many of Dutch origin who arrived after the Second World War, continue to retain the knowledge of dyke building and maintenance. While few local farmers still know how to handle a spade to cut sod into bricks, many understand the appropriate design and the inner workings of drainage and of aboiteaux, as evidenced by the private dykes and aboiteaux that continue to be built. The Department of Agriculture has some of this knowledge, but it needs the experience of the farmers to maintain the dykes.

Community-based management continues today in the 21st century. The farmers of the Grand Pré Marsh Body own the land individually but share resources and make decisions collectively about maintaining the marsh. The farmers do not have direct responsibility for the dykes but retain an essential role in their maintenance and the experience of building them. Their management approach keeps alive the spirit of collective concern for this agricultural landscape and the individual desire to thrive. Throughout the major federal and provincial government projects of the past 70 years, the Grand Pré Marsh Body maintained its role. The Grand Pré Marsh Body’s recorded minutes and archives go back to the late 18th century. It is the oldest and most active organization of its type in North America.

|

|

Centuries of Progress and Adaptation |

|

Many farmers today raise milk-producing cattle and grow crops for their animals. As milk production is a regulated industry, the farmers have a stable means of ensuring their livelihood.

In the past, dykeland was used for crops during summer and as common pasture in the fall. This allowed nutrients in the form of manure to be reintroduced into the soil. The farmers would gather in Grand Pré next to the dykelands to divide the herds into two, one for the east section and one for the west. They would identify individual branding tools, fence the area, brand the animals, and let them loose on the dykelands. That practice continued until the 1970s, when crops became more sensitive to the impact of cattle and when new farming techniques lengthened the season. Today, cattle are still sent for pasturing on the dykeland, but only in specific areas

Starting in the 1970s, farmers placed an emphasis on the surface drainage of these soils. Their method of drainage became known as landforming and involved shaping the surface of a field so that excess rainfall ran off into grassy ditches (see Figure 2–54).

Starting in the 1970s, farmers placed an emphasis on the surface drainage of these soils. Their method of drainage became known as landforming and involved shaping the surface of a field so that excess rainfall ran off into grassy ditches (see Figure 2–54).

|

Landforming in Grand Pré consists of open ditches with a 30-centimetre drop over a distance of 300 metres to drain into the creeks. As a result, the soil dries much faster and holds the heat more efficiently. Farmers can begin working the land earlier in the season and grow a greater variety of crops. Typical crops are pasture, hay, cereals, soy, alfalfa, and some vegetables. During dry summers, dykeland soils hold water better than the upland soils.

Many farmers today raise milk-producing cattle and grow crops for their animals. As milk production is a regulated industry, the farmers have a stable means of ensuring their livelihood. Most of the crops grown on the dykelands are intended as cattle feed for both local consumption and sale. The farmers of Grand Pré are recognized as being progressive in their techniques, tools, and use of fertilizers as well as protective of their traditions. |

Today, 100 per cent of the dykeland is used for agriculture, and the area retains its point of pride of being one of the most productive agricultural communities in Atlantic Canada. That enduring use is evidence of a successful adaptation to the prevailing environmental conditions and community management. Future success is assured by the farmers continuing to be the stewards of this agricultural landscape, the product of hard labour, pride, and centuries of acquired knowledge.

|

|

A Place of Remembrance |

|

Since the early 1980s, the Acadian Days are celebrated annually at Grand Pré at the end of July. It is a week-long event that showcases Acadian culture, arts, and history and typically attracts thousands of people.

At the same time a commemorative event takes place next to the Deportation Cross, on 28 July, the national day commemorating the deportation.

The national day of commemoration of the Deportation was declared by the Parliament of Canada in 2003 and first celebrated in 2005. This was the result of individual and collective efforts from members of parliament, members from the Cajun community in Louisiana, and the Société nationale de l’Acadie who were seeking a formal apology from the British Crown and an acknowledgement of the impact of the Deportation on the Acadians. This came in the form of a Royal Proclamation signed by Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Canada which included the following statements:

The national day of commemoration of the Deportation was declared by the Parliament of Canada in 2003 and first celebrated in 2005. This was the result of individual and collective efforts from members of parliament, members from the Cajun community in Louisiana, and the Société nationale de l’Acadie who were seeking a formal apology from the British Crown and an acknowledgement of the impact of the Deportation on the Acadians. This came in the form of a Royal Proclamation signed by Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Canada which included the following statements:

|

The proclamation concludes with the declaration of a national day of commemoration of the event every year on 28 July, which is the day when the Order of Deportation was signed by the Governor in Halifax in 1755. The proclamation was another important milestone in the public awareness in Canada of the events surrounding the Deportation. The first year was celebrated in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia with the unveiling of the first two monuments to the Acadian Odyssey, marking the location of Deportation and resettlement of Acadians around the world.

It typically includes a ceremony with Catholic priests, Anglican ministers, Mi’kmaq elders, and recently members of other faiths; a mass at the Covenanter Church in Grand Pré; and a walk from that Church to the Memorial Church Since 2005, a multi-faith event has been held at the Deportation Cross at the initiative of local non-Acadian residents (see Figure 2–56).

It typically includes a ceremony with Catholic priests, Anglican ministers, Mi’kmaq elders, and recently members of other faiths; a mass at the Covenanter Church in Grand Pré; and a walk from that Church to the Memorial Church Since 2005, a multi-faith event has been held at the Deportation Cross at the initiative of local non-Acadian residents (see Figure 2–56).

|

This last event is significant as it involves non-Acadians in an important commemorative event. Throughout the years, non-Acadians have played a role in supporting the Acadians’ aspiration to symbolically reclaim Grand Pré. From the early years of the 20th century, when a local jeweller partly of Acadian descent acquired the land and the DAR developed the site for tourism purposes, to today’s local community, non-Acadians have learned about the Deportation and its impact on the Acadians and contributed toward the commemoration of Acadian heritage at Grand Pré. Acadian politician Pascal Poirier noted in 1917 that “the return to Grand Pré is a symbolic resurrection of Acadie [an event] that should not offend our friends and fellow citizens of foreign nationality. On the contrary, a sincere feeling of fraternity and peace oversee this return.” This spirit continues to underpin the relationships in Grand Pré. |

The relationship between Acadians and non-Acadians has been an ongoing exercise of mutual understanding and respect. Grand Pré is not a contested landscape, as the local residents and other non- Acadians have recognized for a long time the Acadian layer of heritage. The local community has been celebrating the Apple Blossom Festival since the 1930s as a means to advertise the agricultural products of the Annapolis Valley but also to celebrate the scenic beauty and Acadian history that was the background to Evangeline.

Recently, during the Acadian World Congress in 2004 and the 250th Anniversary of the Deportation in 2005, the local community worked to welcome Acadians on their ancestral land by hosting them and offering resources to carry out their events. One particularly powerful moment was when a farmer whose family had lived and farmed in Grand Pré since the 1760s offered to host the descendants of the Acadian family that once owned that land. The event was attended by hundreds of people, descendants of the Thibodeau family from Canada and Louisiana, as well as the current landowners, the Shaws.

Actions such as these are important indicators of a mutual desire to understand, remember and learn from experiences. They allow a peaceful, symbolic reclamation by the Acadians of their homeland and are evidence of ongoing efforts towards reconciliation, efforts foreshadowed by Pascal Poirier in the early 20th century when he stated “that [the acquisition of the lands] will result in our return home, here at Grand Pré, owners of our ancestral land, amongst our fellow citizens of foreign ancestry, now our friends.” The landscape of Grand Pré continues to play a central role in the reclamation by the Acadians of their homeland.

Recently, during the Acadian World Congress in 2004 and the 250th Anniversary of the Deportation in 2005, the local community worked to welcome Acadians on their ancestral land by hosting them and offering resources to carry out their events. One particularly powerful moment was when a farmer whose family had lived and farmed in Grand Pré since the 1760s offered to host the descendants of the Acadian family that once owned that land. The event was attended by hundreds of people, descendants of the Thibodeau family from Canada and Louisiana, as well as the current landowners, the Shaws.

Actions such as these are important indicators of a mutual desire to understand, remember and learn from experiences. They allow a peaceful, symbolic reclamation by the Acadians of their homeland and are evidence of ongoing efforts towards reconciliation, efforts foreshadowed by Pascal Poirier in the early 20th century when he stated “that [the acquisition of the lands] will result in our return home, here at Grand Pré, owners of our ancestral land, amongst our fellow citizens of foreign ancestry, now our friends.” The landscape of Grand Pré continues to play a central role in the reclamation by the Acadians of their homeland.

|

|

Commemorative Monuments |

|

The locations of Grand Pré village and Horton Landing have memorial buildings and monuments erected in the 20th century in homage to the Acadian ancestors and their deportation, starting in 1755. The overall property forms the symbolic reference landscape for the Acadian memory and the main site for its commemoration.

EvangelineThe statue of Evangeline was erected in 1920 in celebration of the success of; "A Tale of Acadie,” first published in 1847, a poem written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Millions of people were drawn to the story of a young Acadian couple from the village of Grand-Pré, Evangeline Bellefontaine and Gabriel Lajeunesse, who were separated by the events of the Deportation, followed by a life-time of searching to be reunited. Evangeline became a symbol of the Deportation and the perseverance of the Acadian people.

Horton Landing

|

|