Once the Acadians were removed from their lands, the British endeavoured to attract settlers from New England. In late 1758 and early 1759, they issued inducements to attract land-hungry settlers from those colonies.

|

|

Arrival of the New England Planters

|

|

|

Having addressed the Acadian threat by deporting most of the Acadians, the British authorities sought to address the Mi’kmaq threat by signing treaties with them throughout the 18th century. Indeed, the Mi’kmaq had been allies of the French and the Acadians.

During the Deportation, the Mi’kmaq helped some Acadians escape into the forest and in many instances sheltered them as their own. For the British Crown, these treaties meant peace with the Mi’kmaq and the freedom to settle Nova Scotia with populations whose loyalty was unquestionable.

|

The colonists, known collectively as the New England Planters, arrived in 1760 at Grand Pré, an area they knew by reputation to be a highly productive agricultural district.

What they found instead was that a large portion of the dykeland was submerged.

|

|

After the Acadians were forcibly removed from Grand Pré in 1755, no one was left to carry out routine repairs on the dykes. In November 1759, a great storm struck at the peak of the 18.03-year Saros cycle, when tides are unusually high in the Bay of Fundy and Minas Basin. A sea surge broke the dyke walls at Grand Pré in several places alongside the Gaspereau River, and sea water flooded a large portion of the eastern and western sections of the dykeland. Some of the dykes that had protected earlier enclosures were still intact and stopped the water from invading the entire dykeland.

|

|

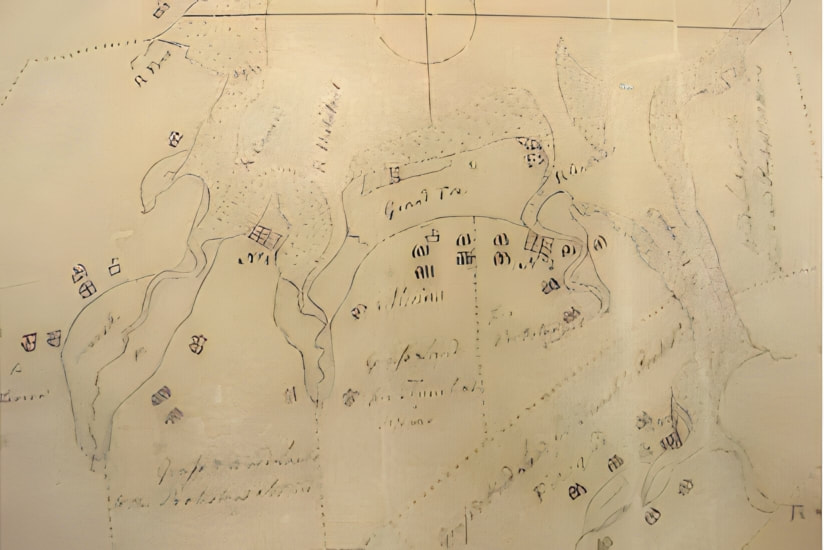

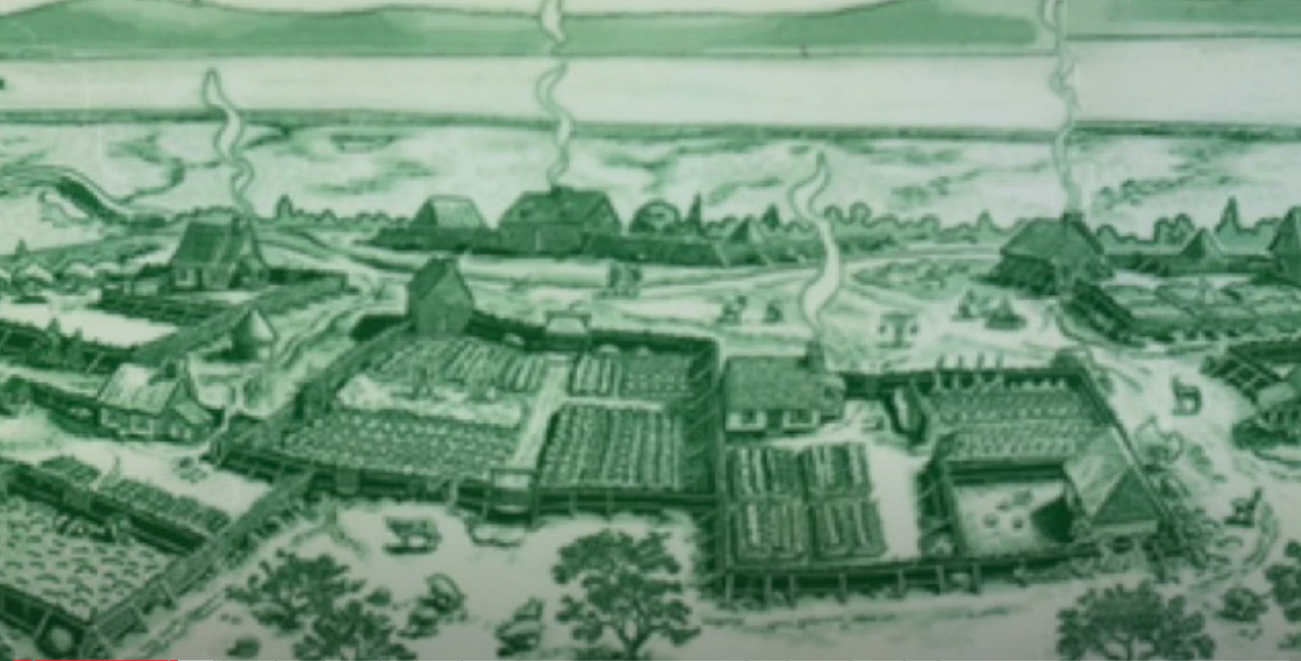

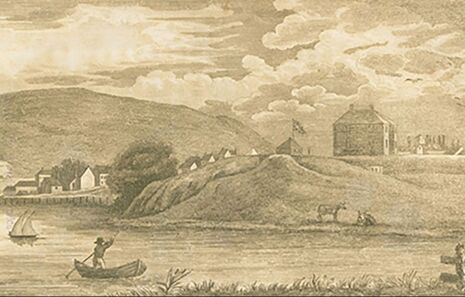

The authorities drew up plans for a town in Horton township based on their typical colonial settlement pattern, a rectilinear town grid with central squares, perched on the highest point of land. For Grand Pré, renamed Horton except for the vast marsh that retained its original French name, the town plot was laid out on the hills adjacent to Horton Landing nearest to the Gaspereau River. The settlers were allocated four types of land: a parcel in the town plot, a parcel of cleared upland, a parcel of dykeland and a woodlot. The New England Planters were directed to settle the town and to relocate existing buildings and erect new ones.

|

In 1759, the British authorities subdivided Nova Scotia into counties for administrative purposes. The County of Kings covered a large area along the Bay of Fundy, including the Minas Basin. The county was divided into three townships: Cornwallis, Horton, and Falmouth. Grand Pré fell within the jurisdiction of the township of Horton. It had the largest amount of dykeland – over 2000 hectares (5000 acres) – and included 1200 more hectares of cleared upland. These conditions were ideal for an agricultural settlement.

|

|

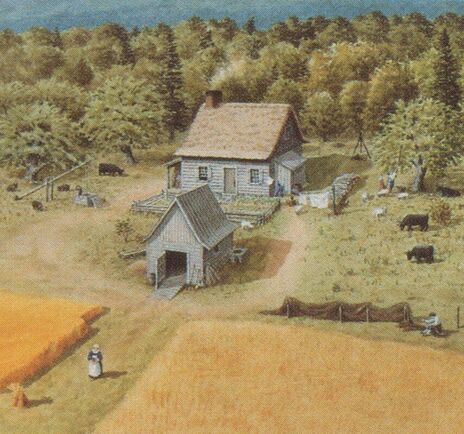

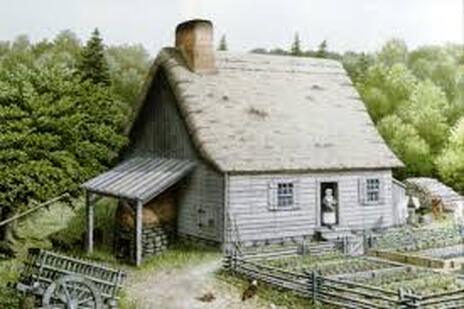

New England Planters were at first not as successful farmers as their predecessors. They knew nothing about drainage on the dykelands, the little need for manure on those lands, the value of ploughing in autumn rather than in spring, and crop rotation, all practices that arose from an understanding of the environmental conditions of an inter-tidal dykeland. Over time, thanks to the knowledge and techniques they learned from the imprisoned Acadians, the newcomers who settled on the uplands at Horton eventually became master dyke builders themselves. They continued the Acadian relationship between the living space on the uplands, the primary farmland on the dykeland, and the woodlots for building materials. The New England Planters expanded the living space farther upland, erecting churches and community halls, and settled on Long Island as well. By 1817, the Governor of Nova Scotia Lord Dalhousie would note, “There is no town of Horton; it is a scattered settlement of neat common houses, small farmers, but rich in their way of life.”

As time went by, the New England Planter settlements at Horton and elsewhere put down deep roots. Much of Horton itself would, in the 20th century, see its name revert to what the Acadians had called it: Grand Pré. Wherever they settled, the New England Planters and their descendants exerted an influence on Nova Scotia’s culture, politics, landscape, and architecture. The best-known standing buildings in Grand Pré associated with the New England Planters are the Crane house (1767), the Calkin house (1768), and the Covenanter Church, constructed between 1804 and 1811. Nearby Acadia University, in Wolfville, also has a link with the New England Planters, although it dates from a few generations later. A Prime Minister of Canada, Sir Robert Borden (1854–1937), is probably the best-known New England Planter descendant. He was born and raised in the village of Grand Pré.

|

The first order of business for the British authorities was to take possession of the dykelands, redistribute them to the new farmers, and ensure that the farmers acquired the skills they needed to maintain the dykes. The interior sections of the Acadian-created dykeland were still protected by dykes, and the authorities immediately distributed them to individual farmers. The sections that had been flooded with seawater in 1759 posed a greater challenge. New England Planters had no experience with dyke building and dykeland farming practices before they arrived in Grand Pré. The British authorities turned to imprisoned Acadians, some of whom were at nearby Fort Edward, for advice, assistance and labour.

The British settlement pattern proved inefficient for the farmers. The four types of land they had been allocated were often scattered across the landscape. As a result, many parcels of land were sold or exchanged. Most farmers wanted to live on their best land, not in a town plot on a promontory. The New England Planters quickly understood the efficiency of the Acadian settlement pattern. As they were under no threat from the French or the Mi’kmaq after the fall of the Fortress of Louisbourg in 1758 and Québec in 1759, they abandoned the town plot in favour of the dispersed and linear Acadian settlement pattern along the dykeland.

It is noteworthy that the Acadian pattern of local ownership and control over the dykeland would be continued when the New England Planters took over Grand Pré in 1760. In fact, the first legislation relating to dykeland was passed by the government of Nova Scotia as early as 1760. It provided for a group of owners to appoint commissions and a Commissioner of Sewers for each dykeland in Nova Scotia. This recognized that building and effectively maintaining dykelands can only be done collectively and locally. The Commissioner would decide what work was required and arrange for labour and the raising of all funds to meet costs associated with keeping the dykes in repair. The farmers would share expenses for dyke maintenance. They would also appoint from among themselves individuals to assess the size and value of dykelands, to “police” the dykelands and monitor the condition of the fields, to verify fences and enclosures, and to perform other similar duties of common interest

|