The Seven Years’ War, sometimes called the first “world war,” pitted Britain against France and involved allied countries on both sides. While France concentrated on the war in Europe, Britain sent 20 000 troops to North America in a bid to bring down France’s colonial empire. The war led to the fall of New France.

|

|

Acadian Deportation 1755 |

|

|

As world events crowded in on Acadian and British settlements in Nova Scotia, the British administration, known as the Nova Scotia Council, decided to revisit the question of Acadian neutrality. They did so more forcefully than in the past, when their control over the province had been more nominal than real. Over the next few years a complex series of events unfolded that culminated in what became known as the Grand Dérangement, the Deportation of the Acadians. This term refers collectively to many separate forcible removals that took place over seven years beginning in 1755.

In the early summer of 1755, the surveyor-general of Nova Scotia, Charles Morris, prepared a detailed plan for the Nova Scotia Council that outlined how the Acadians might be removed from their lands in Nova Scotia and dispersed elsewhere in other British colonies.

|

|

This plan revived a school of thought that dated back to the 1720s when some British officials favoured removing the Acadians from Nova Scotia and replacing them with Protestants, either British or “foreign,” who would be loyal to the British crown. The British had also noticed the value in the fertility of the farmlands owned by the Acadians, which were an economic driver in the area. The idea of attracting “foreign Protestants” surfaced periodically for several decades; even before the British brought over German and Swiss Protestants to establish the new town of Lunenburg in the early 1750s, a British plan of 1748 shows where Protestants might be settled in the Grand Pré area. The 1748 plan shows where the New England Planters would later establish their town. |

|

In June 1755, an expedition put together by acting Nova Scotia Governor Charles Lawrence and Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts captured the two French forts in the Chignecto region, Fort Beauséjour and Fort Gaspareaux. When news reached Halifax that 200 to 300 Acadians had taken part in the defence of Beauséjour – compelled to do so by the French commander of the fort – the authorities in Halifax saw this as a sign of Acadians’ complicity with the French. The Nova Scotia Council decided that all Acadians in the Chignecto region would be rounded up and deported, even if they or a member of their family had not helped to defend the French fort. About a month later, on 28 July 1755, after meeting twice with the deputies of the Acadian communities on mainland Nova Scotia, the Nova Scotia Council resolved to remove every Acadian man, woman and child from all of Nova Scotia. The Deportation would begin at Grand Pré and nearby Pisiquid in early September.

|

While the deportation of the Acadians was about removing a disloyal group, there is no denying that the fertile dykelands at Grand Pré and elsewhere were also extremely important to the British plans for settlement. The acting governor of Nova Scotia, Charles Lawrence, offered the following opinion on 18 October 1755, in a letter to the Lords of Trade in London, England:

… As soon as the French are gone, I shall use my best

endeavours to encourage people from the continent to

settle their lands … and the additional circumstances of the

inhabitants evacuating the country will, I flatter myself,

greatly hasten this event, as it furnishes us with a large

quantity of good land ready for immediate cultivation

endeavours to encourage people from the continent to

settle their lands … and the additional circumstances of the

inhabitants evacuating the country will, I flatter myself,

greatly hasten this event, as it furnishes us with a large

quantity of good land ready for immediate cultivation

The events at Grand Pré were among the earliest and largest of the Deportation. Most importantly, they were recorded by some of the key British participants. The records provide a detailed historical account of the events and their impact on the Acadians, and also set the context for later depictions of Acadian culture. They also provide later Acadians with a snapshot of a transformative event in their cultural history. The following information comes from the two most important sources: the journals of Lt-Col. John Winslow and of one of his junior officers Jeremiah Bancroft.

|

Lt.-Col. John Winslow of Massachusetts's was the officer in charge of rounding up and deporting the Acadians from Grand Pré. He arrived on 19 August 1755 with about 300 New England provincial soldiers. He gave no indication of what was to happen, but gave the impression he was there on a routine assignment. His first act was to establish a secure base of operations, because his force was greatly outnumbered by the 2100 Acadian men, women and children living in the Minas Basin area. For his stronghold, Winslow chose the area around the Grand Pré parish church, Saint-Charles-des-Mines. His soldiers erected a palisade around the priest’s house, the church, and the cemetery, and his troops pitched their tents within that enclosure. So as not to upset the Acadians unnecessarily, Winslow informed community leaders they should remove the sacred objects from the church before it became a military base. By early August 1755, the parish priests of Saint-Charles-des-Mines, and of neighbouring parishes, had already been arrested and brought to Halifax to await their deportation to Europe.

|

|

As August 1755 came to a close and September began, the Acadians of Grand Pré and other nearby villages were harvesting crops from the dykeland and cultivated upland areas. This harvest, although the Acadians could not know it, would be their last in Grand Pré. On 4 September 1755, Lt.-Col. Winslow issued a call for all men and boys aged 10 and older to come to the parish church at three o’clock the next afternoon to hear an important announcement. A similar ploy was used by Capt. Alexander Murray to call Acadian males of the nearby Pisiquid region to come to Fort Edward, on the same day at the same time. In fact, the British had used a similar ruse on 11 August in the Chignecto area to attract and imprison some 400 Acadian men in Fort Beauséjour, renamed Fort Cumberland after its capture, and Fort Lawrence. Winslow and his men had witnessed this just before their departure for Grand Pré.

|

|

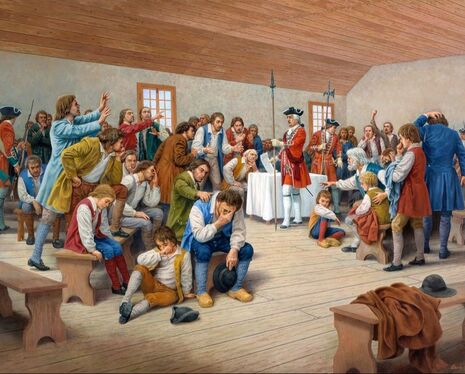

On 5 September, 418 Acadian males of Grand Pré proceeded to their parish church – now surrounded by a palisade and controlled by armed soldiers – to hear the announcement.

Once they were inside, Winslow had French-speaking interpreters tell the assembled men and boys that they and their families were to be deported. Included in the announcement was this statement: that your lands and tenements, cattle of all kinds and live stock of all sorts are forfeited to the Crown with all of your effects saving your money and household goods and you yourselves to be removed from this ... Province.

|

|

Jeremiah Bancroft, one of Winslow’s junior officers, records in his journal that the look on the Acadian faces as they heard the announcement was a mixture of “shame and confusion ... together with anger.” He added that the “countenances” of the Acadians were so altered they could not be described.

[the inhabitants left] unwillingly, the women in great distress carrying off

their children in their arms, others carrying their decrepit parents in their carts and all their goods moving in great confusion and appeared a scene of woe and distress [they] went off praying, singing, & crying, being met by the women & children all the way…with great lamentations upon their knees praying. |

|

Acadians lived together in large, extended family units, and even though Winslow gave orders that families were to be kept together, this often proved impossible in the confusion and because of the small size of the ships. Friends, relatives and neighbours were separated, never to see each other again.

On 19–21 October, the soldiers compelled families from outlying communities to assemble at Grand Pré in preparation for their eventual loading on board transport ships. This group of Acadians numbered about 600, from 98 families. While they waited for the transports to arrive, they lodged in the now-empty Acadian homes near Winslow’s camp, along the upland area by the reclaimed marsh. These families were deported to the Anglo-American colonies just before Christmas 1755. This time the departure point was not Horton Landing but another spot nearby.

In the end, of the slightly more than 14 000 Acadian men, women and children, three quarters were deported to other parts of North America or to Europe. The rest went into hiding or fled.

|

The removal of the roughly 2100 people who lived at Grand Pré and in the neighbouring villages proceeded neither quickly nor smoothly. Winslow had to cope with a shortage of transport ships and provisions. The men and boys spent more than a month imprisoned within either the church of Saint-Charles-des-Mines or on the transports anchored in the Minas Basin before the rest of the population was forced on board the ships. Winslow described the scene of the first contingent of young men, marching from the church along the road beside the dykeland to what today is known as Horton Landing. On 8 October 1755 the mass embarkation of the men, women, and children to the waiting ships began, with the small boats setting off from Horton Landing. Those who lived at Grand Pré and Gaspereau went first.

|

|

Having addressed the Acadian threat by deporting most of the Acadians, the British authorities sought to address the Mi’kmaq threat by signing treaties with them throughout the 18th century. Indeed, the Mi’kmaq had been allies of the French and the Acadians. During the Deportation, the Mi’kmaq helped some Acadians escape into the forest and in many instances sheltered them as their own. For the British Crown, these treaties meant peace with the Mi’kmaq and the freedom to settle Nova Scotia with populations whose loyalty was unquestionable.

|

The Deportation of the Acadians scarred the landscape. In 1755, the New England and British troops burned many Acadian houses, barns, churches and other structures as they depopulated the areas. They wanted to make sure that no shelter was left behind for anyone who escaped Deportation. In the overall Minas Basin area, soldiers set fire to about 700 houses, barns, and other buildings. Colonel John Winslow was on horseback while the British Soldiers are forcing the Acadians to the Shore of Minas Basin known as Horton's Landing, from where they were deported on the arriving ships. |

|

|

The Acadian Odyssey |

|

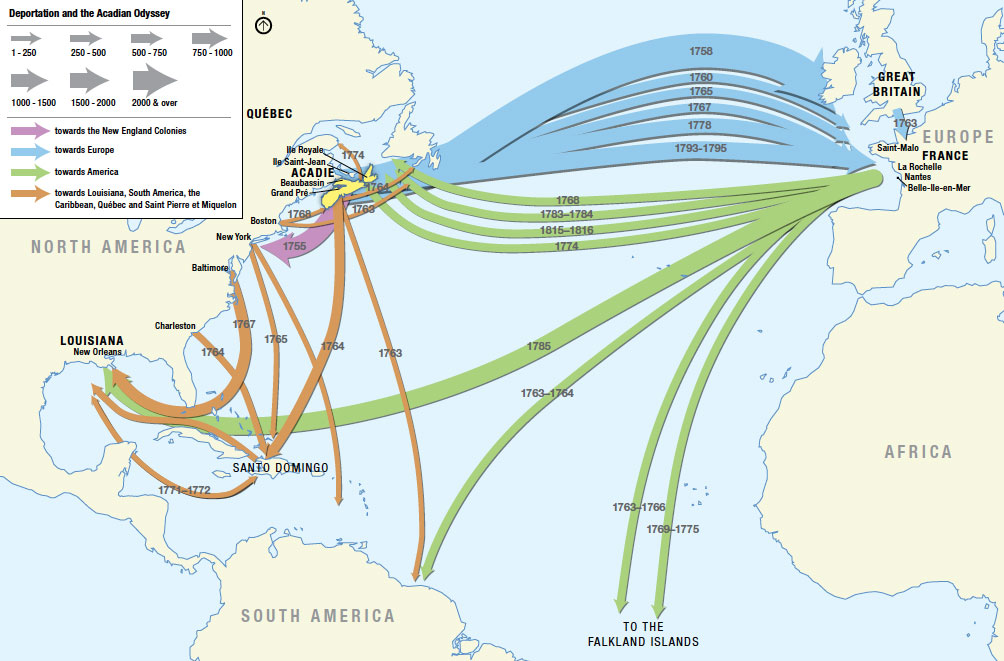

In the coming decades, thousands of Acadians would land at ports around the world, only to depart again in search of a place from which they could one day return to their homeland in Acadie. Out of this Odyssey was born the Acadian diaspora.

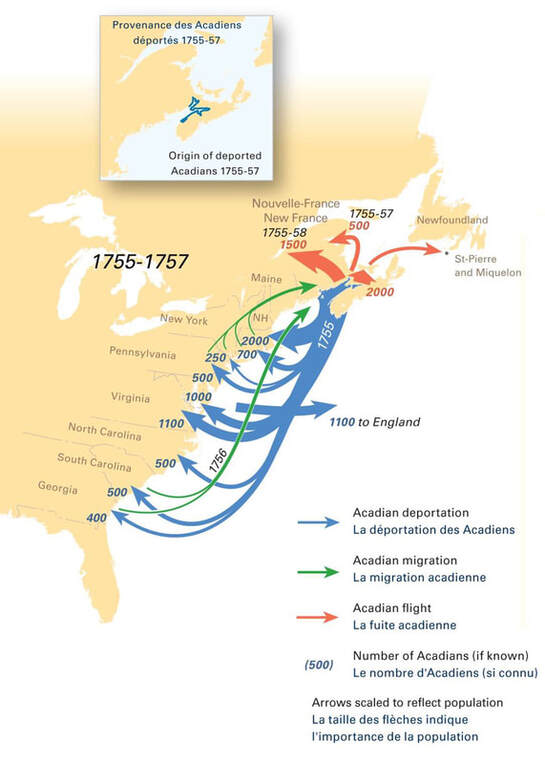

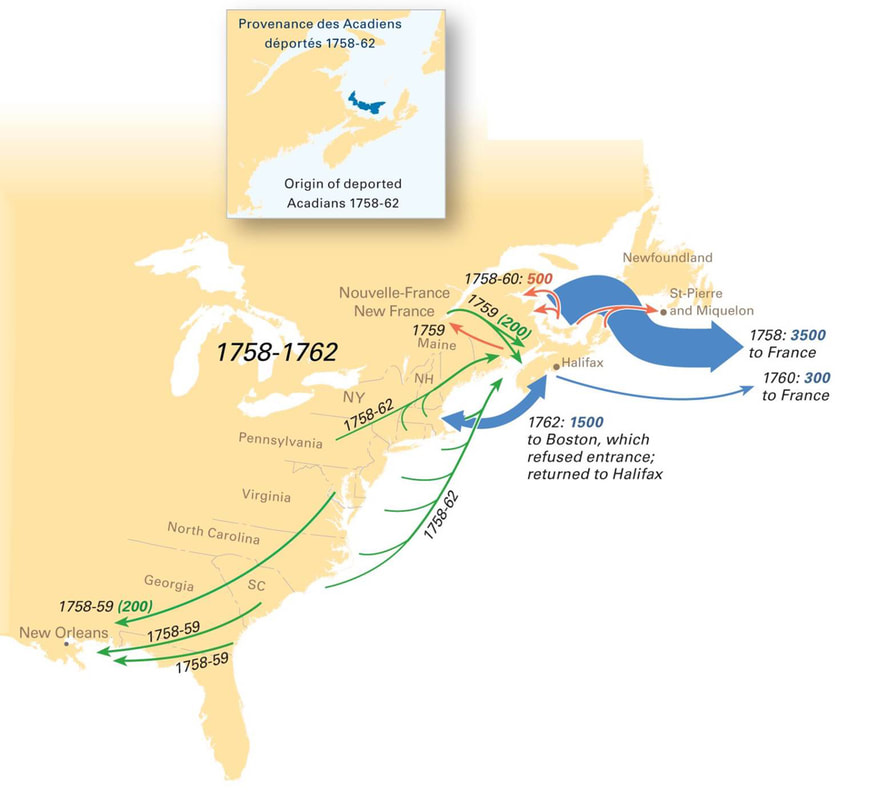

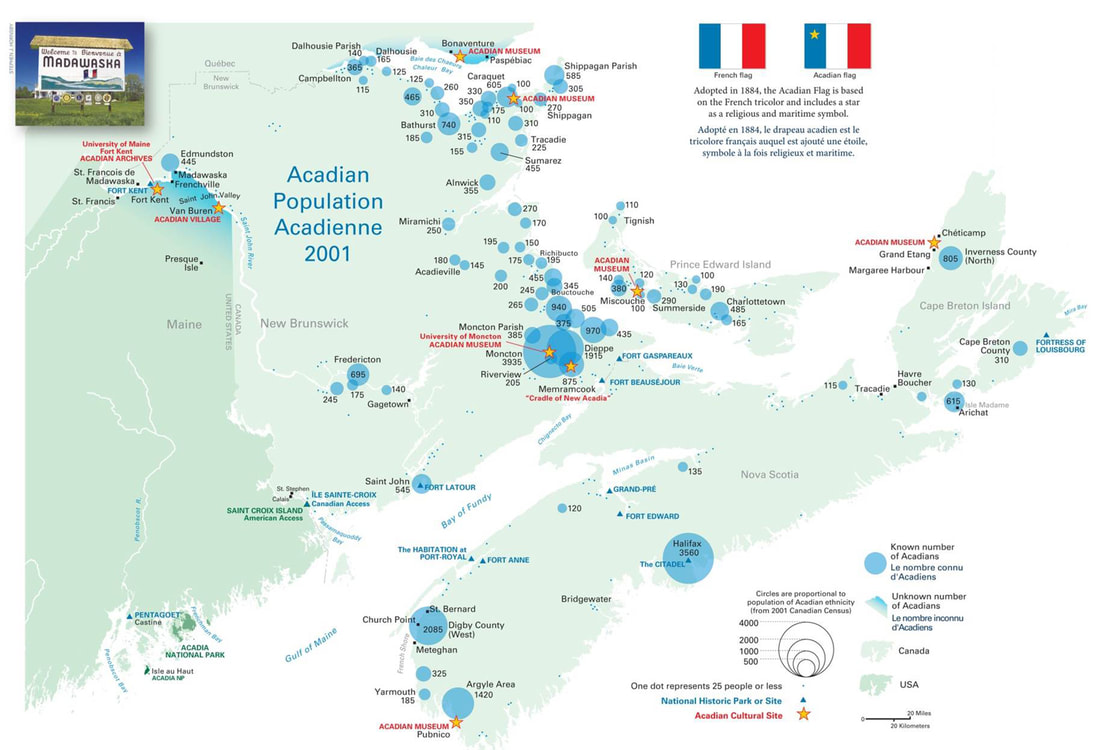

Between 1755 and 1762, the British authorities organized the gathering of Acadian populations in key locations to board ships and sail in convoys to various destinations (see Figure 2–34). In the last months of the year 1755 alone, 6000 Acadians, or close to half the entire population, had been deported: from the Minas Basin area, including Grand Pré, from the Pisiquid area, from Chignecto and Port Royal.

|

In the Minas Basin area that year, a total of 2100 Acadians were removed. This includes the removal, by late October 1755, of over 1500 Acadian children, men, and women – with children by far the largest category – from Grand Pré and nearby villages onto the transport ships. The convoy sailed out of the Minas Basin bound for Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. At the same time, transport ships carrying an estimated 1119 Acadian deportees from the Pisiquid area also sailed south to destinations in the Anglo-American colonies.

These ships formed a convoy as they were joined by those carrying the 1100 deportees from the Chignecto area who were destined for the southernmost colonies of the Carolinas and Georgia. In December, some 1664 Acadian men, women, and children from the Port Royal region were also deported from Annapolis Royal to the Anglo-American colonies.

In the years that followed, thousands more would be deported from Acadie, mainly to France, following the fall of Louisbourg in 1758. Some 4000 Acadian deportees from île Royale (Cape Breton Island) and île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) were deported directly to France in the fall of 1758, as were more than 200 inhabitants from the Cape Sable area in 1758 and early 1759.

In the summer of 1762, another 915 Acadian men, women, and children were deported from Halifax to Boston. The Boston authorities refused to accept them. The ships brought the Acadians back to Nova Scotia, where they were detained as prisoners of war. The movement of the Acadian people is illustrated in Figure 2–34

|

|

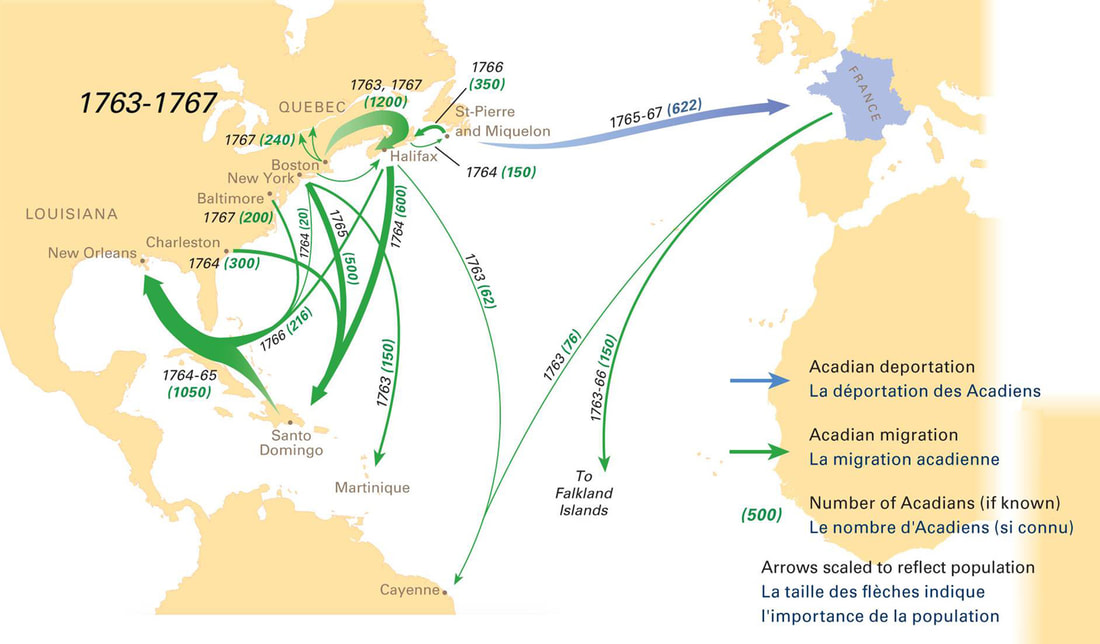

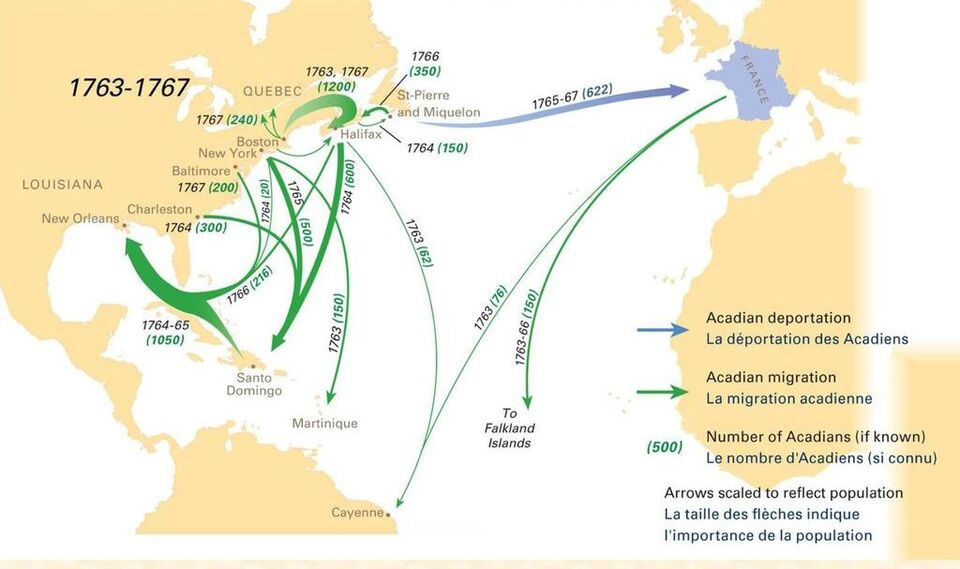

These deportees were sent to different locations, with the intent by Governor Charles Lawrence to “divide [the Acadians] among the colonies … as they cannot easily collect themselves together again.” Some were sent to the New England colonies, whose authorities were required to provide shelter and food.

Many colonies did not wish to take on that burden and did not allow the ships to land, forcing them to continue on to the next port. In many cases, families were separated, children were assimilated into Protestant families, and adults were subject to imprisonment or servitude. In some colonies, the governors were anxious to get rid of the deportees and granted them passports to travel freely between borders, with the hopes that they would move back to Nova Scotia.

Some Acadians, after Virginia refused to welcome them in 1756, were sent as prisoners of war to Britain, where they were distributed among the coastal towns of southern England. These were eventually sent to join thousands of deportees that had made it to France. The return to France did not offer any comfort, however, as there was too little land for them to settle. Many ended up destitute.

|

After the fall of New France in 1760, the authorities in Nova Scotia did not wish to have the Acadians back, even though the British no longer deemed the French to be a threat. Authorities in other parts of Canada needed settlers and were open to attracting the Acadians. The Governor of Québec, James Murray, was one who pursued that idea. In a 1761 letter to Jonathan Belcher, the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia at the time, Murray wrote that Belcher would be ill advised to allow the Acadians back to the lands they had vacated. He argued that it “... must renew to them in all succeeding Generations the miseries the present one has endured & will perhaps alienate for ever their affections from its Government, however just & equitable it may be.” Nova Scotia’s need for settlers prevailed, however, and in 1764 the British authorities gave Acadians leave to settle there again, with certain conditions attached to their return: they could not settle on the lands they had once occupied, and they could not concentrate in large numbers. This latter condition was to prevent them from forming a community. Some 1600, or a little more than 10 per cent of the pre-deportation Acadian population, decided to settle in Nova Scotia and the two neighbouring maritime provinces.

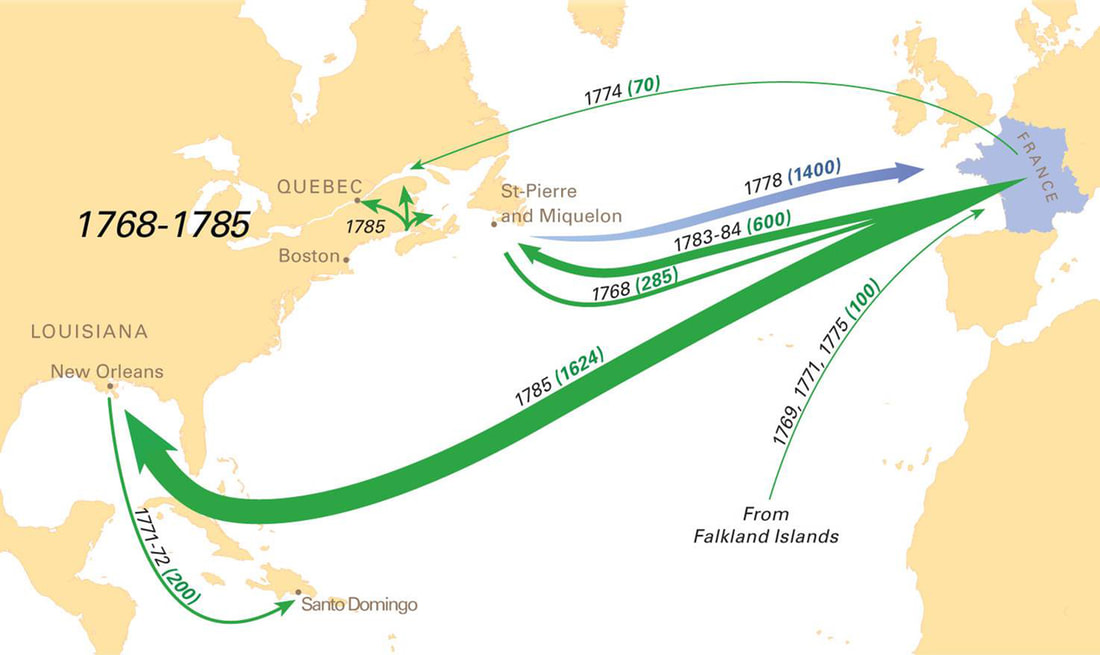

The Acadian regions of present-day Nova Scotia are now hundreds of kilometres away from their former settlements, primarily in the southwest and in Cape Breton. Most of those who survived the Deportation preferred to settle instead in Québec, in France, or in French territory such as Saint-Pierre et Miquelon, Santo Domingo (present-day Haiti), and Guyana. In 1785, some 1584 Acadians made their way from France to Louisiana, then a Spanish colony. They are among the ancestors of today’s Cajuns.

The Acadians who had been deported to France came directly from the conquered French colonies of Ile Saint-Jean and Ile Royale in 1758 and, in 1763, from Virginia via England where they had spent seven years in detention. In total, some 3000 deportees arrived in France in the mid-18th century. They were concentrated in the Poitou area and in Belle-Ile-en-Mer in Brittany. Most were unsuccessful in settling, and the French authorities increasingly considered them a burden. In 1785, two-thirds of them departed for Louisiana. Two decades earlier, in 1763, others had arrived in the French island territory of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon near the coast of Newfoundland in the Atlantic Ocean.

|

They were removed by the French in 1767 and brought back in 1768. In 1778, the British took control of the islands and deported the entire population to France. The islands changed hands several more times before the French recovered them in 1816 and Acadians were finally able to return. Both in France and in its overseas territories, the few Acadian families that settled there eventually adapted to mainstream society but retained a sense of their ancestry and their identity through oral tradition and artistic expressions.

|

Acadians had settled in Louisiana as early as 1764. Some families came from Nova Scotia via Santo Domingo, in 1764–1765, while most of the other families went directly from Maryland and from other Anglo-American colonies, through the Caribbean. They were joined in 1785 by the large group from France that had not succeeded in resettling among the French. Acadians were concentrated principally in southern Louisiana and exerted much influence in politics and in the economy. Until the American Civil War in 1861, Louisiana was a bilingual state where French was actively used in public administration, the courts, and business. Steadily, however, that presence was eroded as mainstream Louisiana society came to view the expression of Cajun (Acadian) culture as inappropriate. Legislation was passed in the early 20th century to integrate Cajuns into mainstream society through the school system. Throughout the 19th century, much as in Acadie, the Cajuns preserved their traditions because of relative isolation. They followed in the steps of Acadians in Canada and adopted some symbols, including Notre Dame de L’Assomption as their patron saint. Music, songs, and other artistic expressions maintained the oral tradition of their story and the collective sense of identity. However, the Cajuns had to wait until the middle of the 20th century to rekindle a severed relationship with their homeland in Grand Pré.

The Acadians who ended up in Guyana and the Caribbean were sent there by the French authorities, whose twofold aim was to relieve the burden on the administration in France and to settle the colonies that France had kept after signing the Treaty of Paris in 1763. From France, the Acadians were sent to settle the Falkland Islands, Guyana, and Haiti. Although some families remained where they had landed, over time the majority made their way to Louisiana. There is little awareness today, in Guyana and the Caribbean, of an Acadian identity at a community level.

In Québec, the Acadians settled in every corner of the province starting in the late 1760s. Mostly concentrated along the St. Lawrence River, they progressively settled in other areas where agriculture was predominant. The province of Québec is where the largest Acadian population was living by the end of the 18th century. Because of the similarities in religion, language, and social status with the Canadiens (French Canadians, today’s Québecois), the Acadians easily integrated into mainstream society. The Acadians who lived in the province embraced the struggle for the rights of French speakers that drove politics and social discourse in Québec throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Despite their integration, these communities maintained an awareness of their ancestry and contact with the Acadian communities of eastern Canada. In the late 19th century, delegates from those communities in Québec attended the national Acadian conventions held in New Brunswick. The largest population of Acadian ancestry is still in Québec.