The Acadian Renaissance was a period of renewed cultural awareness during the 19th century in Canada’s maritime provinces. Its effect then influenced the identity of Acadian communities elsewhere in the world. While each community had its own challenges to overcome in maintaining its identity, for the Acadians who came back to Nova Scotia after 1764 the challenge of returning to their homeland, and making a new home, was enormous. Unable to return to their original lands, Acadians became tenants until, in time, they acquired their own lands.

|

|

Productive Dykeland and

|

|

The first expansion of the dykeland occurred in 1806 on the west side, with the building of the “New Dike” or “Wickwire Dyke”.

It was built west of the north–south Acadian dyke in an area the Acadians had never dyked, in part because of the challenges of resisting the tidal pressure. This dyke enclosed over a hundred hectares of new farmland and withstood the brunt of storms and tides coming from the west. It did not break until 1869, when the Saxby Gale lashed the coast, bringing a combination of high tides and strong winds. As the Acadian dykes had been left in place after the Wickwire Dyke was built, the main Grand Pré Marsh remained relatively untouched. The Wickwire Dyke was rebuilt in 1871. The maintenance and expansion of the dykes allowed farmers to maintain a high level of productivity that was admired by experts and visitors. The foremost Nova Scotian expert on agriculture in the early 19th century, John Young, offered an assessment of the Grand Pré dykeland in 1822. At that point, the dykelands had been in New England Planter hands for about 60 years:

|

The coast of the Bay of Fundy is unquestionably the garden of Acadia, and accordingly we find that the French planted themselves there on the first occupation of the country. They threw across those dikes and aboiteaux by which to shut out the ocean, that they might possess themselves of the rich marshes of Cornwallis and Horton, which prior to our seizure they had cropped for a century without the aid of manuring. … Spots in the Grand Prairies [Grand Pré] of Horton have been under wheat and grass alternately for more than a century past, and have not been replenished during that long period with any sort of manure.

|

|

Writing in the early 1880s, another expert, D.L. Boardman, observed;

[The] Grand Pré Dike [dykeland] is one of the oldest in Kings County and one of the best in the province. The old French had dikes here on the first occupation of the country, and there are now to be seen all over the Grand Pré remains of old dikes within those now doing their duty in keeping back the tide. These have been plowed down and leveled off in places, but it is not a difficult matter to trace them.

|

The American biologist and writer Margaret W. Morley (1858–1923) was clearly impressed by what the Acadians had first achieved and the New England Planters maintained when she wrote in 1905: “[We] cannot gaze upon the broad meadows before the door of Grand Pré without remembering the hands that first held back the sea.”

|

|

The Birth of a Symbol |

|

The Deportation of the Acadians scarred the landscape. In 1755, the New England and British troops burned many Acadian houses, barns, churches and other structures as they depopulated the areas. They wanted to make sure that no shelter was left behind for anyone who escaped Deportation. In the overall Minas Basin area, soldiers set fire to about 700 houses, barns, and other buildings.

|

Those acts of destruction set the stage for the mythological and symbolic aspects of the Deportation. In reality, the village of Grand Pré itself was spared, at least initially. Winslow had his headquarters there, and approximately 600 Acadians were later brought from neighbouring communities and held in the houses for over a month before being sent into exile. Some of the structures at Grand Pré may have been burned after that date. However, sources produced in 1760 describe that at least some – and possibly a good many – of the buildings in Grand Pré were still standing. According to the surveyor general of Nova Scotia, Charles Morris, roughly 100 houses were still standing at Grand Pré when the New England Planters arrived in the spring of 1760. One of those buildings was apparently the church of Saint-Charles-des-Mines. Regardless of the extent of the destruction, the rupture has been symbolically expressed in oral tradition and the collective memory of the Acadians as they recounted a destruction by fire and the desolation of the land following the removal of the population.

|

In the early 19th century, certain individuals and organizations began to commemorate the bygone Acadian presence at Grand Pré. Two major forces were at work. One related to the historical, literary and artistic works that linked Grand Pré more than any other pre-1755 Acadian village to the Acadian Deportation. The other was the Acadian renaissance that began in the latter half of the 19th century throughout the maritime provinces of Canada. Together, the two forces combined to overlay the agricultural landscape with a symbolic landscape.

|

|

Evangeline, A Tale of Acadie |

|

The most influential of the many literary works connected with Grand Pré was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem Evangeline, A Tale of Acadie, published in 1847. The poem tells a love story about two fictional characters, Evangeline and Gabriel, yet it was based on a tale Longfellow had heard of a young couple separated at the time of the Deportation.

|

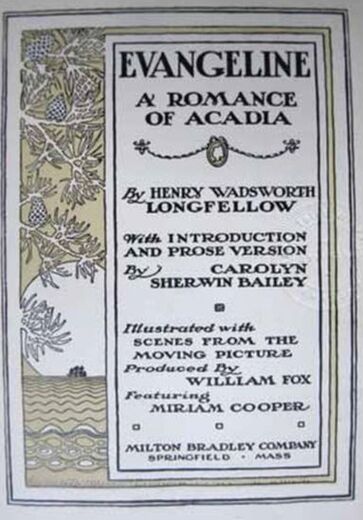

The American poet was not the first to write about the upheaval in a literary form, but his characters and plotline became by far the best known and were instrumental in creating Grand Pré as a symbol. Longfellow’s description was loosely based on Thomas Chandler Haliburton’s An Historical and Statistical Account of Nova-Scotia (1829), in which the historian described the events at Grand Pré in 1755 by presenting material from the eyewitness account in John Winslow’s journal. Grand Pré, a real place with a real history, became the opening scene for a fictional work that for the next century would become the best-known interpretation of the Acadian Deportation. Over the next 100 years, Longfellow’s Evangeline went through at least 270 editions and 130 translations. The first foreign-language adaptations were in German and Polish in 1851. French and Danish followed in 1853, Swedish in 1854, Dutch and Italian in 1856, and so on around the globe. Illustrated editions began to appear in 1850, and over the next 150 years dozens of artists offered their visual (and often fanciful) interpretations of Grand Pré and other locales. When motion picture technology was developed, the story of Evangeline and the Acadian Deportation soon turned up in cinemas. Short, onereel adaptations of Longfellow’s tale were produced in 1908 and 1911. In 1913, the first feature-length film ever produced in Canada was a five-reel production of Evangeline that lasted over an hour. American film versions of the Evangeline story were released in 1919 and 1929. |

|

Though the Evangeline phenomenon began among non-Acadians, first the Americans and then the British, it was quickly embraced by Acadians and other Francophones (see Figure 2–38).

They often came to know the story through the French-language adaptation written by Pamphile Lemay in 1865 and revised in 1870. Lemay’s adaptation differed significantly from the original poem by Longfellow, yet the central characters were the same, the opening setting remained Grand Pré, and the narrative arc was essentially the same.

|

|

Longfellow generated a high public awareness of the Acadians’ story and of its link with Grand Pré. He was followed by many others who physically transformed the landscape so that it symbolically reflected the attachment of the Acadians to their homeland, commemorated the Deportation, and displayed symbols of their values. In 1869, at the newly opened Grand Pré railway station, the Windsor and Annapolis Railway Company hung a sign that read: “Welcome to the Land of Evangeline and Gabriel.” The next year, the first organized tour by rail of the “Land of Evangeline” brought Americans from Boston. Acadians were not involved. In 1895, an article by historian Henri L. d’Entremont appeared in the principal Acadian newspaper L’Évangéline, in which the author argued that Acadians needed to honour their ancestors at the emerging tourist site at Grand Pré. This article, along with political speeches and other public appeals, raised Grand Pré as a place of significance in the Acadian consciousness. A little over a decade later, Acadians took their first concrete steps to commemorate Grand Pré, following the renaissance of their culture and identity. |

|

|

The Acadian Renaissance |

|

Throughout the ordeal of their wandering, Acadians held onto their culture. It survived in part because they were relatively excluded from the predominant society, and in part because they maintained strong oral traditions. Folklore was passed on between generations and within each small community. Following the resettlement of some Acadians in Nova Scotia, communities began rebuilding on the foundations of their French language, their Catholic faith, and their family ties. These settlements were small and dispersed, as required by the conditions set for their resettlement. This added to the difficulty of maintaining a sense of community, especially within the larger context of a new and very different social and political structure. The strong foundation of Acadian culture allowed the elite to build a sense of national Acadian identity.

The story of the Acadian forced removal had shocked British society at the time, but this sentiment provided no tangible opportunities for rebuilding Acadian society or acknowledging the wrongs they had suffered. In fact, those opportunities only materialized in the middle of the 19th century with the publication of the poem Evangeline, A Tale of Acadie. While entirely fictional, its success allowed the real story of the Deportation to be heard and communicated to the world.

The publication of Evangeline was a seminal moment in the emergence of the Acadian Renaissance. First, it was written in English, which brought it to many readers in North American and British society. Second, it emerged in elite circles of New England, a region with which Nova Scotia had close ties, both because of the history of the New England Planters and because of the many Acadian deportees who found themselves in New England after the Deportation. That connection provided the conditions for Evangeline to become equally popular among English speakers and Acadians. Evangeline was, even as fiction, the first public acknowledgement of the events that had surrounded the forced removal of the Acadians almost 100 years earlier.

The story of the Acadian forced removal had shocked British society at the time, but this sentiment provided no tangible opportunities for rebuilding Acadian society or acknowledging the wrongs they had suffered. In fact, those opportunities only materialized in the middle of the 19th century with the publication of the poem Evangeline, A Tale of Acadie. While entirely fictional, its success allowed the real story of the Deportation to be heard and communicated to the world.

The publication of Evangeline was a seminal moment in the emergence of the Acadian Renaissance. First, it was written in English, which brought it to many readers in North American and British society. Second, it emerged in elite circles of New England, a region with which Nova Scotia had close ties, both because of the history of the New England Planters and because of the many Acadian deportees who found themselves in New England after the Deportation. That connection provided the conditions for Evangeline to become equally popular among English speakers and Acadians. Evangeline was, even as fiction, the first public acknowledgement of the events that had surrounded the forced removal of the Acadians almost 100 years earlier.

|

The story of Evangeline quickly resonated with the Acadian religious and social elite, who saw an opportunity to enhance their own efforts to build a strong community and claim rights for it. The characters in the poem and their story embodied the values that the Acadian elite recognized in their own people, and they inspired a gradual period of political, economic, and social empowerment. Evangeline, the main character, and her devotion to her lover Gabriel throughout her ordeal became a symbol of the power of faith in a greater purpose. Her belief echoed the message from the Catholic Church to the Acadians and illustrated the perseverance of the people in the face of adversity. These characteristics, and the values of sacrifice, obedience, and resignation to life’s ordeals, were consistent with the church’s teachings, thus making Evangeline acceptable. The Catholic Church authorized the reading and even the teaching of Evangeline as a means to raise the cultural awareness, sense of identity, and history of the Acadians. As the educated elite became immersed in the story and the emotions surrounding the Deportation, they now had a medium for conveying that story and a set of symbols to supplement the oral tradition with which they had grown up. Most importantly, Evangeline provided a tangible setting as a focus for the Acadians’ cultural reawakening. Grand Pré was introduced to the collective memory of the Acadian people. It became a point of reference, so much so that the expression “the children of Grand Pré” was used in political discourse of the time to refer to the Acadians. It embodied the lost homeland, the symbol of what Acadians aimed to return to, and the evidence of the wrongs they had suffered.

|

The Catholic Church’s acceptance and promotion of this poem was important at a time when it played a key role in Acadian society and provided the tools for its renaissance. The Church was a driver in building the Acadian national identity, providing, amongst other things, access to education and their language and symbols. In 1854, the first Acadian school of higher learning, the Collège Saint-Thomas, was founded in Memramcook, New Brunswick. In 1864, it became the Collège Saint-Joseph under the authority of the Congregation of the Holy Cross and obtained degree-granting status, later becoming a university. During the 1880s, the Acadians of the Maritimes began to hold “national conventions,” following the participation of Acadians in French Canadian political gatherings in Québec, to defend the interests of their community. Their focus was to achieve cultural objectives by promoting the use of the French language in education and in the political, economic, and religious spheres. The Church played an instrumental role, along with the educated elite, in leading these conventions. The first convention was held in 1881 at the Collège Saint-Joseph in Memramcook where most of the young Acadian elite who took part in these patriotic events had been educated. The delegates to that convention created the Société nationale L’Assomption, whose mandate was to promote and defend the interests of the Acadian people in Atlantic Canada. The second convention took place in Miscouche, Prince Edward Island, in 1884. At that convention, the Acadians adopted a national feast day (15 August), a patron saint (Notre Dame de l’Assomption), a flag (the French tricolour with a gold star in one corner, an anthem (Ave Maris Stella) and a motto (L’union fait la force – unity makes strength).

By the end of the decade, Acadians had three French weekly newspapers, the oldest one being the Moniteur Acadien, founded in 1867 in Shédiac, New Brunswick, and members of their elite were elected to the highest offices of the province and the country. By the beginning of the 20th century, Acadian folklore had acquired status along with these symbols to entrench the foundations of Acadian identity. All these manifestations of social empowerment became sources of pride and self awareness.

The Acadian Renaissance was a period of social and political transformation of the Acadian community of Canada in the late 19th century. Through various collective acts, Acadians acquired a sense of unity, in spite of the original British intention to keep them dispersed. Embracing the wave of nationalistic consciousness that moved through Europe and North America in the 19th century, the Acadians elected to reclaim their presence in eastern Canada through incremental actions that gave them the tools for political, economic, and cultural empowerment. An important step was to choose symbols of identity such as a flag, a patron saint, and an anthem, and to tell a national story, all adopted in part or in whole by Acadian communities of the diaspora. Grand Pré grew to become the location to anchor that identity, those symbols, and the collective memory.

The Acadian Renaissance was a period of social and political transformation of the Acadian community of Canada in the late 19th century. Through various collective acts, Acadians acquired a sense of unity, in spite of the original British intention to keep them dispersed. Embracing the wave of nationalistic consciousness that moved through Europe and North America in the 19th century, the Acadians elected to reclaim their presence in eastern Canada through incremental actions that gave them the tools for political, economic, and cultural empowerment. An important step was to choose symbols of identity such as a flag, a patron saint, and an anthem, and to tell a national story, all adopted in part or in whole by Acadian communities of the diaspora. Grand Pré grew to become the location to anchor that identity, those symbols, and the collective memory.

Acadian Anthem

Ave Maris Stella

Dei Mater Alma

Atque Semper Virgo

Felix Coeli Porta

Acadia my homeland

To your name I draw myself

My life, my faith belong to you

You will protect me

Acadia my homeland

My land and my challenge

From near, from far you hold onto me

My heart is Acadian

Acadia my homeland

I live your history

I owe you my pride

I believe in your future

Ave Maris Stella

Dei Mater Alma

Atque Semper Virgo

Felix Coeli Porta

Ave Maris Stella

Dei Mater Alma

Atque Semper Virgo

Felix Coeli Porta

Acadia my homeland

To your name I draw myself

My life, my faith belong to you

You will protect me

Acadia my homeland

My land and my challenge

From near, from far you hold onto me

My heart is Acadian

Acadia my homeland

I live your history

I owe you my pride

I believe in your future

Ave Maris Stella

Dei Mater Alma

Atque Semper Virgo

Felix Coeli Porta